Investors' Outlook: Cut! That’s a wrap.

"Year of the bond", "year of interest rate cuts", "year of the recession": 2024 has already been given many labels. Whichever label investors choose, it is clear that the end of the most aggressive interest rate hikes in four decades has now arrived and the fog is clearing. Now it's the turn of the next scene.

Outlook for 2024

Things don’t always turn out as expected, and 2023 served as yet another reminder of that. Among the events that caught investors off guard were the shockwaves rippling through financial markets, triggered by inconspicuous names such as Silvergate Capital and Silicon Valley Bank, and the ensuing collapse of an iconic Swiss bank, or the downgrade of the US sovereign rating and Hamas attacks in Israel, followed by tensions in the Red Sea. So, what may 2024 have in store?

The Multi Asset Boutique reiterates its economic baseline scenario for the time being, which still pencils in a US recession. There’s a plethora of reasons for this out-of-consensus call: Monetary policy works with long and variable lags, and the impact of higher interest rates has yet to fully seep into the economy.

Consumers and businesses alike face tight lending standards, and, unlike last year, fiscal stimulus is unlikely to come to the rescue given a deeply divided US Congress and the upcoming presidential elections. There doesn’t seem to be a significant growth impulse out of China that would support global growth. And companies’ cautious stance on capital expenditure also indicates weakness ahead. On a positive note, inflation probably won’t be too much of a burden. While pushing inflation back to the Fed’s 2 percent target may be challenging, a flare-up in form of a strong second wave is unlikely. Global goods shortages have eased, many companies have built up significant inventories, and China is even exporting deflation into the world. US core inflation data (excluding food and energy prices)—a key input for the Fed—is now also quickly moving towards target.

2024 may well throw the world the occasional curveball. One key factor to watch is the US labor market, which has started to soften but remains astonishingly resilient. The absence of job cuts in the next few months would make a soft landing increasingly feasible.

Will US consumers continue to be the economy’s supporting actors?

Investors kept a keen eye on the world’s largest economy last year, with many anticipating a recession. One of the reasons it didn’t come knocking in 2023 was the continued resilience of US consumers. They kept on spending—in part boosted by accumulated pandemic savings and a strong labor market—and helped the economy stave off a recession. But for how much longer?

Consumers are tightening their belts in many parts of the world. In Europe, private consumption collapsed almost at the same time as the European energy crisis in 2022 and has still not recovered. Chinese consumers started to exercise restraint much earlier—namely since the outbreak of the Covid-19 pandemic.

But the situation in the US is different. Consumer spending, which accounts for around 70 percent of US gross domestic product, has—seemingly unperturbed—continued its pre-pandemic trend. This strong consumption data is quite surprising. One would expect consumers to curb their spending amid high interest rates, a weakening economy, and the fact that real income (i. e., nominal income adjusted for inflation) has been stagnating for some time. Instead, true to the motto “you only live once” (colloquially known as #YOLO), they are spending even more than before (see chart 1).

Broken dreams of home ownership, solid asset growth, strong labor market

There are several reasons for consumers being in a spending mood. First, they seem to be playing catch-up after the restrictions imposed by the Covid-19 pandemic (in the form of the much-cited “revenge spending”). Second, the tight housing market is discouraging many consumers from saving. A typical US family no longer has enough income to qualify for a mortgage on a median- priced home, according to the National Association of Realtors’ Housing Affordability Index. At the same time, interest rates for a 30-year fixed mortgage remain quite high, at just under 7 percent. This means that what is arguably the biggest item of expenditure is becoming a more distant prospect, so many may ask why they should put money aside. Third, consumers are increasingly lulled into a false sense of security. In past recessions, consumers could count on the government to come to the rescue with generous stimulus packages. Many seem to believe that this will be the case again. So-called excess savings are another important reason. The data here can be very difficult to interpret as it’s prone to rather substantial revisions. However, it can be assumed that consumers have more savings than originally thought. There are other positive wealth effects as well. Anyone who has invested in equities or property over the past five years has seen substantial gains. This is likely to have boosted spending. However, switching to a new mortgage still comes with high financing costs, and most owners are holding on to their existing properties. The bulk of these assets, therefore, remain illiquid. US households are also in a better position today than they were in the past. The debt service coverage ratio of private households was around 5.8 percent in the third quarter of 2023, in line with the pre-pandemic level. Here, it is important to highlight that many consumers locked in favorable financing conditions during the era of low interest rates and their exposure to the consequences of higher rates is limited.

#YOYO vs. #YOLO

However, there are some indications that #YOLO could soon be replaced by #YOYO (“you’re on your own”). Consumers are struggling with persistently strict credit conditions (see chart 2). In addition, the cost of taking on new debt is high. The average credit card interest rate in the fourth quarter of 2023 was over 21 percent. Also, the government seems unlikely to provide much fiscal stimulus in 2024. In view of the upcoming US elections on November 5, it is unlikely that the divided Congress will pass significant additional spending. Neither the Democrats nor the Republicans are likely to have any incentive to make concessions to each other.

The most important reason is and remains the labor market, which continues to be strong by historical standards (see chart 3). If it does not weaken noticeably, a slump in consumption, and thus a slump in economic growth, seems unlikely. The Multi Asset Boutique assumes that the labor market will weaken. Companies have now slowly but surely begun to scale back their capital expenditure plans, cut open job positions, and reduce prices. Higher unemployment and lower consumption are likely to follow.

A rollercoaster year for the 10-year Treasury bond

Hopes for rate cuts, easing inflation, and historic yield dynamics: The 10-year US Treasury bond went through a remarkable journey in 2023.

Initially, during the turbulent banking crisis in March, it plummeted to a low of 3.3 percent and roared back to 5 percent in October. On the final trading day of 2023, the yield settled just shy of 3.9 percent. Reflecting on the entire year, this closing figure represented an overall change of just 1 basis point (bp). In terms of total return, the 10-year Treasury bond effectively dodged a third successive year of negative total returns, avoiding an unparalleled series in its historical performance (see chart 1).

Inflation is evidently easing, and the Fed appears ready to begin cutting rates this year. At the time of writing, Fed funds futures have factored in six rate cuts for 2024, aiming for a target policy range of 3.75 percent to 4 percent. The Fed’s Summary of Economic Projections in December indicated that the average policymaker anticipates three rate cuts to 4.75 percent, while the typical forecaster surveyed by Bloomberg expects about four.

So, what explains this inconsistency?

Some market participants continue to expect, or protect against, a possible hard landing where the US economy enters a recession. The Secured Overnight Financing Rate options market suggests roughly a 25 percent chance of the Fed funds rate falling to 3 percent or lower by December. The most probable outcome, however, is for three to four rate cuts this year.

Looking at the end of hiking cycles since the beginning of the 1980s, one might get a sense of what is in store for the 10-year Treasury bond yield. The last hike occurred on July 26, 2023—more than 170 days ago. The yield on the 10-year Treasury bond stood at 3.9 percent, not far from today’s levels. In all previous cycles, yields declined after the last rate hike. If history is any guide, then the yield on the 10-year Treasury bond could be 100 bps lower by the end of this year (see chart 2).

Risk assets, especially high-yield bonds, have had an exceptional performance over the past year, although they have shown signs of losing momentum more recently. The expected excess return looks vulnerable to any bout of spread widening. The current 12-month break-even spread— which indicates the margin of safety for corporate bonds—seems unattractive: if the yield premium rises to this level, high-yield bonds will no longer offer any additional return over 12 months compared to government bonds with the same maturity.

A memorable year for equities

Stock investors can look back on a remarkable year. Against all odds, equities ended up delivering the best absolute return, pulling through a year in which many expected a recession, a possible second wave of inflation, and the bond market outperforming stocks. Global equities capped the year near their record highs, and about 20 percent above strategists’ estimates on average.

Stocks’ solid performance that began in late October 2023 continued in December, albeit at a slower pace than in November. Cooling inflation and the expectation of an approaching Fed pivot were powerful catalysts, resulting in an impressive comeback and creating an almost perfect reversal from what transpired in 2022 (see chart 1).

The S&P 500 Index rose more than 26 percent, while the Euro Stoxx 50 Index climbed nearly 20 percent last year. The Magnificent 7 — Apple, Microsoft, Amazon, Alphabet, Nvidia, Meta Platforms, and Tesla—delivered more than 100 percent of absolute return. Excluding technology stocks, the return was 8 percent. The same is true for the Eurozone, where technology and financials accounted for about 50 percent of the absolute performance.

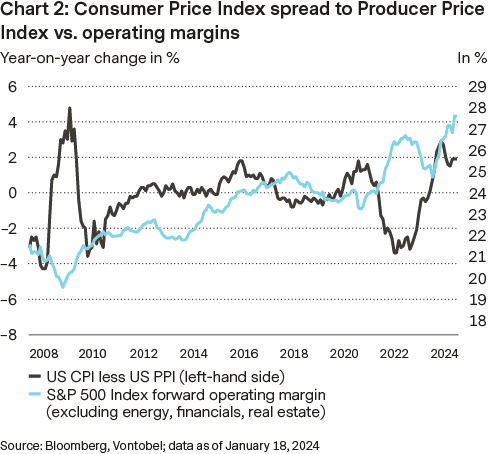

Estimated real 2023 year-on-year earnings-per-share growth is now in negative territory in most markets, implying an easy comparison base for 2024. Additionally, Producer Price Indexes across developed markets have been trailing the Consumer Price Index for more than a year now. Historically, this boosted margins for manufacturing industries (see chart 2), which could eventually lead to positive earnings surprises and mitigate the impact of a recession. Finally, central bank pivots will be a major driver.

Red-hot tensions in the Red Sea

In 2023, oil prices were whipsawed by fears over slowing economic growth, the output policy of the Organization of the Petroleum Exporting Countries and its allies (OPEC+), and the tensions in the Middle East.

The problem at the moment is not that demand is outright terrible. While there are some pockets of weakness, global oil consumption is back to pre-Covid levels. The problem is that there is simply too much supply. In view of the OPEC+ cartel’s repeated production cuts, non-OPEC+ members have ramped up their own production (see chart 1). Some OPEC+ members, such as Iran and Russia, have also surprised markets with larger-than-expected output.

Closed waterways as a tail risk

Investors’ attention has returned to the Middle East in recent weeks, where Houthi rebels’ attacks on shipping vessels in the Red Sea sparked fears of an escalating conflict and disrupted trade flows. Of particular concern is the Bab el-Mandeb Strait, which serves as a vital link between the African and Arabian Peninsulas.

Some 8.2 million barrels of liquids were transported via the Red Sea each day in the January-November 2023 period, according to data by analytics firm Vortexa. Breaking that down, 2.9 million barrels were northbound (Europe), 3.9 million were southbound (Asia), and the remainder were imports or exports within the region. Roughly 70 percent of southbound shipments were of Russian origin, according to Vortexa.

At present, southbound shipments have largely been spared. While tankers carrying Russian oil continue to sail through the Red Sea, others are rerouting around the Cape of Good Hope. This results in longer journeys (a trip from Singapore to Rotterdam now takes roughly 10 days longer) and higher costs (see chart 2).

What about the Strait of Hormuz?

It is dubbed the world’s most important oil chokepoint, as more than 20 percent of global petroleum liquids for consumption flow through it. Fears have risen that Iran, which secured strategically important islands in the Strait some five decades ago, might try to limit or block access to the Strait.

While such an escalation could push prices significantly higher, it doesn’t seem very likely. Iran has repeatedly threatened to close the Strait in the past but has not followed through (its own economy depends on the Strait as well). Even during the 1980–1988 Tanker War, when Iran and Iraq (notably both OPEC members) engaged in attacks on each other’s ships, passage was still possible. Iran is likely also going to be mindful of its key trading partners, particularly China. In the absence of such a shock, oil should trade in the range of USD 70 to 85.

US dollar and the Swiss franc: Currency crossroads

In 2023, the US Dollar Index (DXY) experienced its first annual decline in three years as the Fed indicated the conclusion of its tightening cycle. This shift led to market expectations for interest-rate reductions, potentially starting as early as March.

In all, the DXY pulled back from its high in October 2023 and closed the year 2.1 percent lower (see chart 1). At the onset of the new year, the US dollar is gathering strength after somewhat stronger data fueled expectations that the Fed won’t be rushing to lower interest rates.

As the US economy shows signs of slowing down in the coming quarters, the US dollar’s dominant position, which it has maintained over the past three years, is expected to gradually diminish. The more rapid decrease in inflation in the US compared to G10 countries will likely prompt a more dovish shift by the Fed, potentially reducing the US dollar's interest rate edge more significantly than anticipated.

Ambitions for the strong Swiss franc vs. economic realities

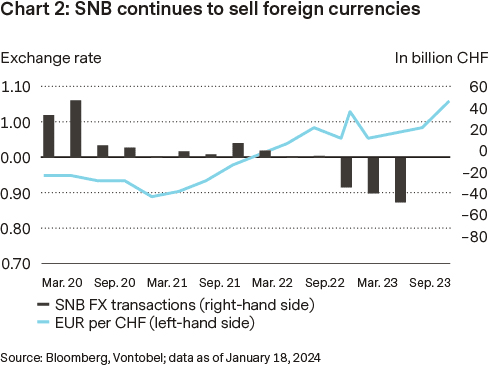

Over the past two years, the Swiss National Bank's (SNB) desire for a stronger Swiss franc has had a major positive impact on the currency, but as inflation starts to subside and the economy decelerates, this goal may become increasingly questionable. The SNB’s total intervention amounted to CHF 22 billion in 2022 and ballooned to CHF 110 billion by the end of the third quarter of 2023 (see chart 2).

In the third quarter, the SNB marginally decreased its foreign exchange sales as the Swiss franc neared its current peaks against the euro and the US dollar. During the period from July to September, Switzerland’s central bank engaged in the sale of foreign currencies totaling CHF 37.6 billion, a reduction from the CHF 40.3 billion sold in the preceding quarter.

By purchasing its own currency and offloading foreign exchange reserves, the SNB bolsters the exchange rate while simultaneously shrinking its substantial balance sheet. This approach has been instrumental in safeguarding Switzerland from the global surge in inflation. SNB Chairman Thomas Jordan has raised concerns about the appreciating Swiss franc. Speaking at the World Economic Forum in Davos at the end of January, he highlighted the possible effects of this trend on the SNB's capability to sustain inflation above zero within the country’s economy. This led to speculation that policymakers might begin cutting interest rates sooner than other central banks, or they could even take steps to limit the currency's appreciation.

Authors

Frank Häusler, Chief Investment Strategist

Stefan Eppenberger, Head Multi Asset Strategy

Christopher Koslowski, Senior Fixed Income & FX Strategist

Mario Montagnani, Senior Investment Strategist

Michaela Huber, Cross-Asset Strategist