Investors' Outlook: Checking for storm damage

Tariffs remain one of the most disruptive forces in global markets, and although the winds have died down, we are still far from grasping the full extent of the damage. Currently, the markets linger in anxious silence after the eye of the storm has passed, leaving behind significant uncertainty.

Lingering clouds

Clouds have started to gather over the US economy as both consumers and companies try to find their way through the fog of trade-war fallout. While peak trade uncertainty may (hopefully) be behind us, the economy has already taken a hit.

Despite tough talk, the bond market seems to have made US President Donald Trump blink. In a surprise U-turn, he announced a 90-day tariff pause, pulling most rates back to “only” 10 percent. Trade adviser Peter Navarro expects a number of deals will be made during the pause period.

But financial sentiment has turned. After months of optimism, recession fears are back on the radar. Nearly half of money managers now see a global downturn as the most likely scenario within a year, according to Bank of America’s Global Fund Manager Survey. Many investors are wondering whether the US is inevitably headed toward a recession. “Soft data”, like sentiment surveys, has already slumped. The worry now is that “hard data” such as US labor market indicators will follow. While March’s jobs report surprised to the upside and initial jobless claims—considered a close to real-time proxy for layoffs—are trending down, other high-frequency signals like job postings on Indeed suggest weakening ahead.

The Multi Asset team believes a sharp downturn can be avoided. Consumers have deleveraged significantly since the financial crisis, and corporate balance sheets remain sound. It also expects more stimulus ahead. Inflation has largely normalized, opening the door to rate cuts for several central banks. Still, the US Federal Reserve is under pressure. After Fed Chair Jerome Powell resisted calls for immediate cuts, Trump publicly chastised him, sparking fears of political interference that weighed on US Treasuries and the dollar. The Multi Asset team believes the Fed will eventually have to cut rates if the labor market falters—prioritizing employment over price stability, if needed.

From “Mar-a-what-now?” to “charismatic chefs”

The historic Mount Washington Hotel in Bretton Woods (1944), Kingston—Jamaica’s capital, nestled in the Blue Mountains (1976), and New York’s iconic Plaza Hotel (1985): history shows that world leaders have a knack for sealing major economic deals in the grandest of avenues. Could Donald Trump’s private Mar-a-Lago estate soon join that illustrious list?

When Stephen Miran published his policy paper, “A User’s Guide to Restructuring the Global Trading System”, in November 2024, it sent shockwaves through the economics world. Those who worked their way through the dense 40-page document were met with a bold claim: the root of global trade imbalances lies in the persistent overvaluation of the US dollar that prevents the balancing of international trade. According to Miran, the dollar’s special status as the world’s reserve currency is at the heart of the issue—artificially inflating the cost of US exports, cheapening imports, undercutting US industry, and ultimately costing American jobs.

Miran proposed tariffs not just as a way to correct global trade imbalances, but also as a means to generate much-needed government revenue. An even more effective approach, he wrote, would be for other economies to appreciate their own currencies and devalue the US dollar, at least those economies that want to continue to benefit from the protective hand of the US military and / or wish to receive trade concessions. He also floated the idea of a coordinated currency agreement, where central banks of key US trading partners would agree to a coordinated dollar sale. Another possibility: imposing a kind of “user fee” on foreign holders of US Treasuries, including sovereign wealth funds and central banks.

Trump appeared to take a liking to what he read. Just a month after the paper’s release, Trump nominated him to lead the White House Council of Economic Advisers. In the months that followed, speculation mounted that Miran was the driving intellectual force behind Trump’s increasingly aggressive tariff agenda and frequent gripes about the strong dollar. Talk of a potential “Mar-a-Lago Accord” began to circulate—one that could include a deliberate devaluation of the dollar.

By late March, however, Miran was already dialing things back. In a Bloomberg interview responding to questions about jittery markets, he clarified that the paper had “taken on a life of its own” against all his intents. It was more like a “recipe book”—a catalogue of available options. Some are easy, some tough, some filling, satisfying meals, and others, he quipped, will leave you hungry again in half an hour. Ultimately, Miran said, it’s Trump who plays the role of “chef”, choosing which ingredients he wants to use.

The chef has been cooking up his own ideas for a while

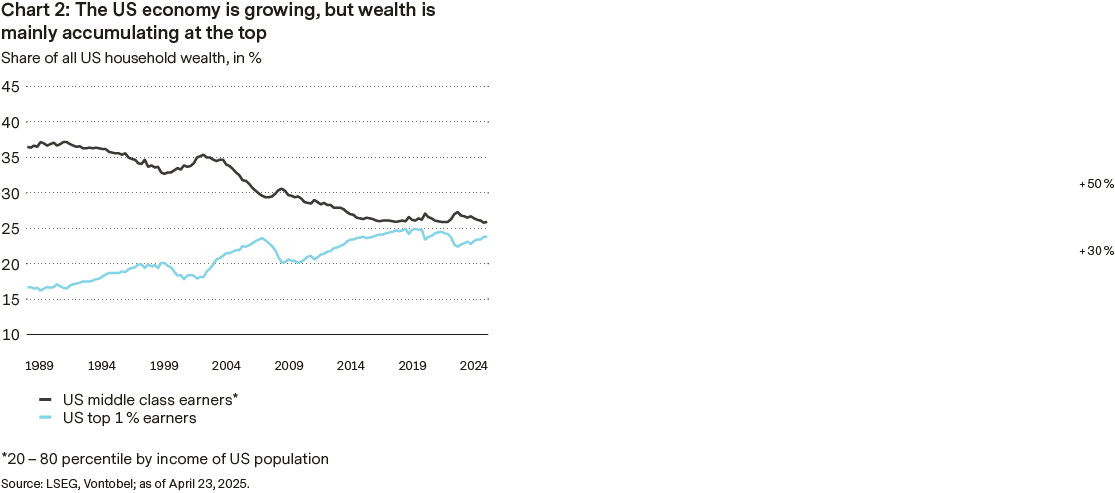

US Treasury Secretary Scott Bessent recently noted that Trump had sensed 40 years ago that American workers never truly recovered from the “China shock”—China’s rapid rise as a global economic powerhouse (see chart 1).

The result, he argued, has been a deep and lasting wealth imbalance: while some prospered, others were left behind and hollowed out (see chart 2).

Quality of life declined. So did life expectancy. And the US, he said, stopped making “things” (see chart 3)—especially the kinds of things critical to national security.

The Covid-19 pandemic only drove the point home, laying bare just how fragile and dependent global supply chains had become. In short: after decades of Wall Street coming out on top, it’s now supposed to be “Main Street’s” turn.

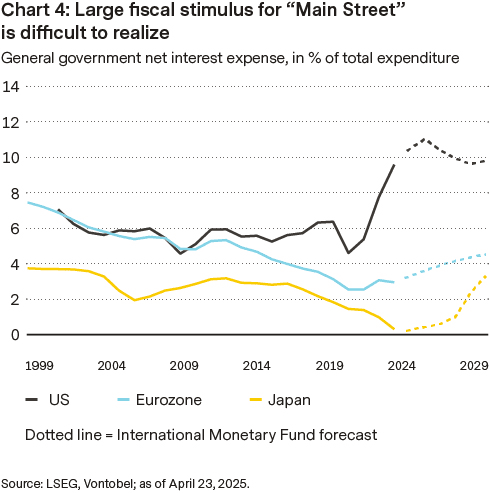

But giving Main Street a boost—through measures like cutting taxes on service workers’ tips—requires money. And with the national debt already sky-high and interest payments ballooning, sweeping stimulus packages are a tough sell. That’s where tariffs come in (see chart 4).

According to Bessent, the administration expects its new tariff policy to bring in between USD 300 billion and USD 600 billion annually.

As for the market turbulence triggered by the tariffs? Bessent didn’t see a reason to change course. He pointed to the early Reagan years as a precedent, calling them “very choppy”. At one point, a furious farmer even showed up at the US Federal Reserve with a shotgun, threatening to kill then-Chair Paul Volcker for raising rates. Still, he said, the tough approach paid off: Reagan won re-election in a landslide, and markets ultimately bounced back (see chart 5).

Why the recipe might not work

The Multi Asset team is skeptical that Trump’s plans—or those of his fellow “chefs”—will be implemented in full. The level of uncertainty across so many fronts is simply too high.

First, Trump’s unpredictable trade policy is driving extreme market volatility. In March, the US Trade Policy Uncertainty Index soared past 5,700 points—up from just 44 a year earlier. With that kind of unpredictability, many companies are choosing to delay investment decisions.

Second, US consumer inflation expectations are spiking. According to a University of Michigan survey, Americans now expect inflation to reach nearly 7 percent over the next year—a level not seen since the 1980s. As a result, people are rushing to buy things they fear will soon cost more, while putting off non-essential purchases amid growing economic unease.

Third, the Fed now finds itself in a monetary policy trap. Chair Jerome Powell recently cautioned that the US is facing very fundamental political shifts with no modern precedent. According to Powell, Trump’s tariffs are expected to slow economic growth and drive unemployment higher. Yet at the same time, they’ll likely stoke inflation. Given this delicate balance, Powell said it would be best to hold off further interest-rate cuts until there’s more clarity. Fed Governor Christopher Waller struck a similar tone, admitting that, like many others, he’s struggling to piece together a coherent picture from so many moving parts.

There’s another growing issue that shouldn’t be underestimated: public sentiment is souring. Trump’s domestic approval ratings have taken a sharp hit since “Liberation Day”. In Canada, bruised by the trade war, the Liberal Party—long critical of Trump—has staged a political comeback. Some cafes have even stopped selling “Americanos”, opting instead for the now-trendy “Canadianos”. Across the Atlantic, enthusiasm for US travel is fading.

According to the International Trade Administration, the number of visitors from Western Europe fell 17.2 percent in March 2025, with German tourist numbers plunging by 28.2 percent. That may help explain the recent dip in prices for flights, hotels, and rental cars. Bloomberg Intelligence estimates that nearly USD 20 billion in tourist spending could be at risk.

But perhaps the most important argument? “Main Street” is still going hungry. Since “Liberation Day”, long-term US Treasury yields—and with them, mortgage rates—have spiked, as foreign investors offloaded US bonds. That makes borrowing more expensive for the government. The sell-off in what are usually considered “safe” Treasuries is striking—especially given that recession fears are on the rise (see chart 6).

What could happen next?

It appears the bond market may have finally forced Trump to reconsider. Just hours after unveiling his new reciprocal tariffs, the chef backpedaled, issuing a 90-day delay on most of them. One of his sous-chefs, trade adviser Peter Navarro, quickly followed up with a new goal: 90 trade deals in 90 days. Hopefully, as many of these deals as possible will actually be completed. Otherwise, there may be a risk that Trump and his team end up spoiling the recipe—and the “Great Plan” could quickly spiral into a recession.

Caught in the drift

President Donald Trump’s trade war continues, characterized by unexpected developments and shifting rhetoric. A universal 10 percent tariff on most imports to the US has been implemented, with higher levies targeting China. This move is expected to impact the economy and may prompt the US Federal Reserve to adopt a more nuanced approach to interest-rate cuts, balancing inflation concerns with overall economic stability.

Following a high-profile announcement from the Rose Garden on April 2, Trump scaled back parts of the proposed reciprocal tariffs. Nonetheless, a 10 percent levy on nearly all US imports remains, while tit-for-tat escalation has driven tariffs on most Chinese goods to 145 percent. Without a major rollback, these tariffs are poised to significantly influence economic growth, with uncertainty already taking a toll on consumer and business sentiment.

US interest rates have shown sharp volatility, driven by a combination of weakening appetite for US assets and signs of investors unwinding leveraged bond bets (see chart 1).

Bond markets stabilized only after news of the tariff reprieve.

The impact of tariffs on inflation presents a more complex picture. A Fed model forecasts an increase in the core Personal Consumption Expenditures Price Index (which excludes food and energy), with the strongest inflationary pressures in the first year, followed by moderation and a decline below initial levels in subsequent years. This suggests the inflation impact may, in fact, be transitory.

The Fed now faces a complex policy conundrum: whether to respond to a short-lived uptick in inflation or look past it, as models suggest it will fade. Two main scenarios are likely to emerge for the Fed. One involves reducing the planned rate cuts this year to counter inflation risks—though this could raise recession risks by driving up unemployment. The other is to disregard the temporary inflation spike and proceed with, or even accelerate, rate cuts to support employment and economic stability. This latter scenario reflects what the market is anticipating (see chart 2).

Ultimately, the Fed’s strategy will likely be a compromise: a delay in immediate cuts, followed by more substantial cuts later if the economy shows signs of weakening and the labor market deteriorates. This middle-ground approach aims to manage temporary inflation without stifling economic and job market activity.

Watching the undertow

Markets experienced historic turbulence around “Liberation Day” on April 2, 2025, when Donald Trump announced sweeping tariffs: a 10 percent base rate on all imports and higher levies on over 90 countries. The move sparked global market chaos—prompting Trump to change course less than a week later.

The initial reaction on April 2 was a brutal selloff, wiping out USD 5 trillion in the S&P 500 Index’s value in two days, as fears of a global recession gripped investors. Though presented as a push for US economic dominance and fair trade, the tariffs shattered market sentiment. The Nasdaq and S&P 500 saw their worst three-day drops since the pandemic. Hong Kong’s Hang Seng plunged 13 percent; its steepest one-day fall since 1997. The VIX spiked to 55, levels last seen during the Covid-19 crisis.

A surprise 90-day tariff pause on April 9 – excluding China—sparked a massive relief rally. The S&P 500 recorded its best day since 2008, while the Nasdaq jumped to its second-largest daily gain on record. Global markets followed suit: Japan’s Nikkei surged nearly 10 percent, and European equities rose 5 percent. Treasury Secretary Scott Bessent called the pause a move to create “maximum negotiating leverage,” signaling de-escalation. Markets rallied again on April 25 after Trump suggested a possible thaw with China. Meanwhile, early first-quarter earnings, likely aided by pre-tariff stockpiling, and intact supply chains for now, are exceeding analysts’ expectations.

All’s well that ends well? Not quite. Stocks face tailwinds and headwinds. On the bullish side, recession fears seem to be priced in now, with sentiment deeply bearish—especially in the US, where mega-cap tech stocks’ underperformance traces more to January’s “DeepSeek moment” than tariffs. The VIX is flashing a contrarian buy signal, and Trump has softened his tone, with talks with China underway soon. Hard economic data remains solid, too—for now.

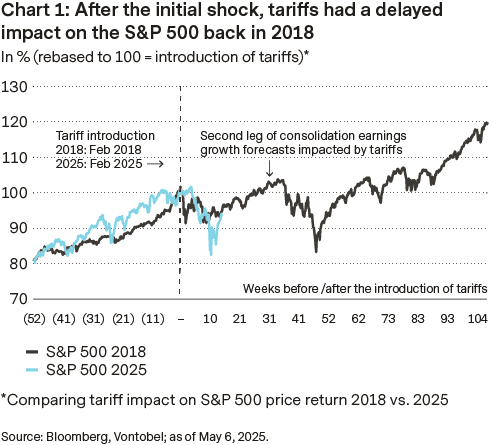

Still, risks loom. Trade war effects often lag (see chart 1).

In 2018’s US-China conflict, earnings forecasts dropped over 10 percent two quarters in, hitting zero. That round hit about USD 400 billion in imports, mostly from China. Today’s tariffs affect 10 times that volume, across more countries, at higher rates, and through more complex supply chains—amplifying potential damage. The lack of earnings downgrades so far may reflect a delay, not immunity (see chart 2).

Weak sentiment surveys, limited Fed support due to raising inflation concerns, and fragile market calm suggest caution may still be warranted.

Gold’s Groundhog Day

In the modern classic movie “Groundhog Day”, a grumpy weatherman is stuck reporting the same story over and over again. Writing about the price of gold these days feels oddly similar. Repetitive, yes, but far less grumpy thanks to gold’s stellar performance.

Once again, gold has surpassed even the most optimistic forecasts this year. Strong and sustained central bank demand, combined with rising geopolitical tensions, have been supporting the precious metal for some time. With Donald Trump’s re-election, trade policy uncertainty, and the economic growth concerns that come with it, have added further fuel to the rally.

That may also help explain the sharp uptick in inflows into gold exchange-traded funds (ETFs) in recent months (see chart 1).

According to data from the World Gold Council, gold ETFs attracted 226.5 tons in the first quarter alone, valued at more than USD 21 billion. ETF investors had previously stayed on the sidelines for quite some time. In the run-up to the dreaded “Liberation Day” on April 2, gold jumped by more than USD 100 per ounce within just a few days—only to give back those gains shortly after. One key reason: a wave of market panic. As margin calls kicked in, some equity investors were forced to liquidate their winning gold positions to raise cash.

But the rally really picked up steam after Trump publicly called Fed Chair Jerome Powell a “loser” and called for immediate interest-rate cuts. His combative rhetoric sparked concerns about the Fed’s independence and damaged investor confidence in traditional safe havens like US Treasuries and the dollar. Gold surged past USD 3,500 an ounce—up 30 percent year-to-date in dollar terms.

So, is gold still “fairly valued” at these levels? Technical indicators suggest otherwise. The Relative Strength Index stood at 80 at the end of April (with anything above 70 considered overbought). At times, gold also traded more than 30 percent above its 250-day moving average (see chart 2).

Historically, such elevated levels have at times been followed by double-digit pullbacks.

Gold is poised to have room to run in today’s world, but short-term corrections are possible.

Under pressure

US policy uncertainty and fears of an economic slowdown have pushed the US dollar to its lowest level since 2022. Traders remain bearish, while the euro gains ground, supported by narrowing growth differentials and increasing fiscal stimulus in Europe relative to the US.

The dollar has declined sharply as Donald Trump’s tariffs have rattled global markets. The world’s reserve currency has weakened alongside US equities and bonds, as fading economic outperformance and aggressive trade approach cast doubt on the country’s policy trajectory.

Once the favored currency, the dollar is losing its allure—a sharp reversal from earlier this year, when Trump’s proposed tax cuts and tariffs fueled expectations of a dollar rally. The outlook is now tilting downward, particularly if concerns about a policy-driven US slowdown persist.

The euro has gained unexpectedly from US trade moves, climbing after the “Liberation Day” tariff news (see chart 1), as market concerns over a US economic slowdown outweighed expected rate cuts by the European Central Bank.

The euro is also buoyed by proactive European fiscal steps, including Germany’s spending boost and EU-wide investments in defense and infrastructure, which may help offset tariff fallout.

This shift is evident in currency options markets, where bullish bets on the euro have increased. Despite questions about EU policy effectiveness, growing skepticism toward US policies has weakened faith in the dollar’s stability. The greenback’s typical positive correlation with cross-asset volatility has faltered, falling amid heightened global macro volatility. This challenges its traditional role as a reliable safe haven.

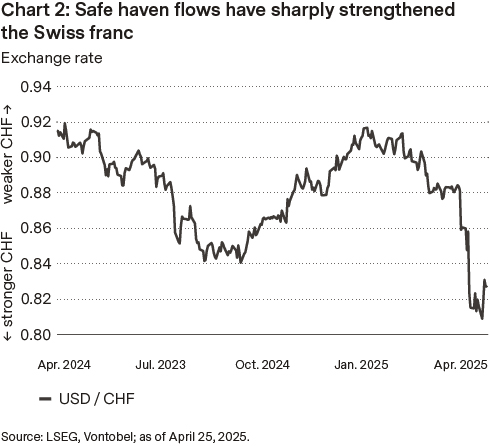

Swiss franc rally fueled by search for safe havens amid US tariffs

As attention focused on Trump’s tariff plans, Switzerland quietly reported March inflation at just 0.3 percent year-over-year—below expectations. Inflation is expected to stay under target through year-end. In the meantime, tariff-driven uncertainty has led to safe haven flows, which have sharply strengthened the Swiss franc (see chart 2).

This could add to deflationary pressure in Switzerland. With low inflation and a strong franc, intervention by the Swiss National Bank (SNB) would normally be expected. But US scrutiny of currency practices may limit that option. Instead, the SNB may first step up its rhetoric about lowering interest rates toward zero or below to curb franc strength.