Investors’ Outlook: Traversing risky terrains

April has once again shown us how immediate and severe the impact of geopolitical tensions can be on an investment portfolio. For some time, many investors have been mainly concerned about the labour market, interest rates and inflation. Now, they are gradually realising that not only the economic but also the geopolitical situation can trigger the dreaded 'black swan'. The conflict in the Middle East escalated further when Iran attacked Israel for the first time in history. This worried investors, who feared a potential conflict in the region involving the United States. Meanwhile, the war in Ukraine continues, with Russia planning an offensive in the near future. Tensions between China and Taiwan are another concern for investors. In addition, the historic election year of 2024 is likely to divide society in the US.

April showers

Growing geopolitical tensions in the Middle East were among the most alarming “showers” of April, with investors closely monitoring the possibility of an escalation and its potential effects on the market. In the meantime, central banks and the timing of interest-rate cuts also remain primary considerations.

Amid strong consumer spending and a resilient labor market, US economic data has continued to surprise to the upside. This translates into stickier-than-expected inflation, which is likely to make the latter stages of the US Federal Reserve’s (Fed) inflation fight more difficult. It also means that the first interest-rate reductions will probably occur later than originally anticipated, as Fed Chair Jerome Powell indicated last month, saying that policymakers can keep rates steady for “as long as needed” should price pressures continue.

Nevertheless, investors are still eagerly awaiting the month of June. The Eurozone economy is showing signs of improvement, according to leading indicators: the bloc’s manufacturing and services industries appear to be growing, inflation has slowed sharply, and industrial production in the region’s biggest economy, Germany, rose more than expected. The European Central Bank (ECB) is now planting the seeds for a first interest-rate cut. ECB President Christine Lagarde said in a CNBC interview in mid-April that the central bank is “heading towards a moment” where it must moderate its restrictive monetary policy, barring any “major shock.” Other ECB members echoed that tone.

US presidential election— what a second Trump term could mean for investors

The US presidential election may still be a while away; the world’s largest economy won’t head to the polls until November 5, 2024. But a glance at the major financial news outlets and social media channels quickly reveals that the election campaign is already in full swing.

Incumbent Joe Biden and Donald Trump have recently engaged in verbal blows over which of them was better suited to the presidency. Trump, 77, has called Biden “grossly incompetent”, while Biden, 81, when asked about his advanced age, replied, “One candidate is too old and mentally unfit to be president … the other guy is me.”

Attempting to make a call on who will end up moving into the White House is about as helpful as flipping a coin. It probably doesn’t make a lot of sense to try to predict the election outcome by using probability calculations. However, thought experiments and asking “what if” questions can be helpful to investors.

In this article, the focus is on Trump as opposed to Biden. This is not due to any political tendencies or any conviction that Trump has better chances at winning. Rather, it reflects the likelihood that a second Trump term would have greater market implications than the re-election of Biden. A Biden re-election would be more likely to result in a continuation of the status quo.

Why a second Trump term should seriously be taken into consideration

Trump’s first term in office (2017 – 2021) was eventful: from a trade war with China to the withdrawals from the Iran nuclear deal and the Paris climate agreement and threats to pull out of alliances such as the North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO) or the World Trade Organization (WTO), his presidency was also marked by numerous personnel changes, entry bans for certain population groups, the construction of the US-Mexico border wall, impeachment proceedings, stolen secret papers, electionfraud allegations, and an armed storming of the Capitol.

So, one might think that the hurdles for a second term would be high. However, polls currently indicate a tight race. And the situation doesn’t look too bad in the fiercely contested swing states either. Moreover, Trump ended up doing better than polls suggested in the past.

What speaks in favor of Trump?

His lingering popularity probably has a lot to do with social developments and Trump’s status as the “enfant terrible” of the establishment. Take, for example, the increasingly frustrated US middle class, which has felt left behind as globalization has lifted many formerly low-income people into the middle class and benefited developing countries like China in recent decades. In the 1990s, the middle class owned around 37 percent of private household wealth in the US. At the turn of the millennium, this figure fell to around 30 percent. Today, it’s just under 26 percent, according to Fed data.

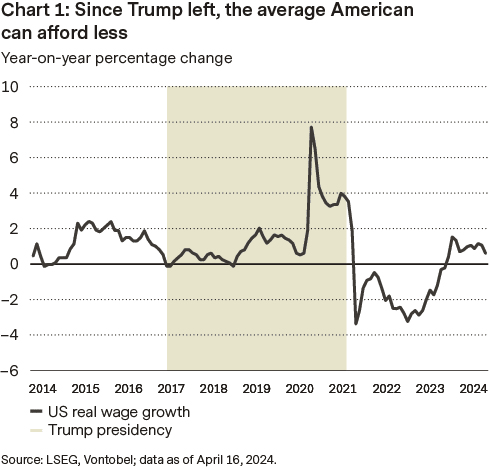

At the same time, trust in state institutions has been declining for years. According to a Gallup poll[4], trust in the Supreme Court was just under 60 percent in the 1980s. In 2023, it was only 27 percent. Only trust in newspapers (2023: 18 percent) or Congress (2023: 8 percent) looks worse. These long-simmering developments have worsened since Trump’s departure. One important reason is likely to be the inflation shock, which pushed the real (i.e., inflation-adjusted) wage growth of many Americans into negative territory at the start of 2021 (see chart 1).

What also plays into Trump’s hands is Biden’s unpopularity. A president’s approval rating is normally a good predictor of his chances of re-election. In the past, the public’s opinion of the president depended primarily on their assessment of the economy. Recently, however, this relationship has been turned upside down: The US economy is strong, the unemployment rate remains at a historic low, and even inflation (the groundwork of which was laid before Biden took office) has declined significantly. And yet, Biden’s approval rating has plummeted. While his approval rating stood at 53 percent at the beginning of 2021, it’s now at around 40 percent, according to ABC News-owned website FiveThirtyEight. This makes him even less popular than Trump was during his first term.

Many Americans don’t trust Biden to tackle issues that are important to them, according to an Ipsos survey. This applies in particular to social issues such as crime or immigration. The latter has increased significantly since 2022 (partly due to easing pandemic restrictions) and has intensified since. In December alone, federal agents encountered 10,000 people a day crossing the southern border of the US, according to Bloomberg News. That’s poised to be a breeding ground for populist slogans.

In addition, one of the Democrats’ most reliable voting blocs appears to have shifted its opinion. According to an April New York Times / Siena poll, Trump’s support among black voters has climbed to 16 percent. Hispanic voters are also warming to Trump. One possible explanation could be that these groups are disillusioned with Biden and are particularly affected by negative real incomes.

What speaks in favor of Biden?

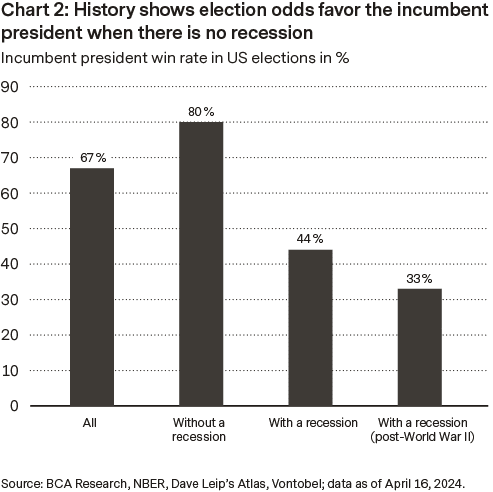

The statistics are on Biden’s side. Historically, the incumbent US president is re-elected 67 percent of the time. If the incumbent president manages to avoid a recession, that probability increases to 80 percent. However, if the economy slips into a recession, the president is penalized, and the rate drops to 44 percent (see chart 2). In view of the strong labor market, both in the US in general but also in swing states, it currently looks as if a recession could be avoided before the election.

Who will win Congress?

Another important question is who will win Congress. Two scenarios have the highest probability: either a “red wave” (significant gains for the Republicans) or a stalemate. A “blue wave” (significant gains for the Democrats) is less likely.

Why? Congress is divided into the Senate and the House of Representatives. In the Senate, 28 Democratic seats are up for re-election this year; 23 Democratic seats are not up for election and are therefore considered to be “safe”. The situation is different for the Republicans: only 11 seats are up for re-election, and 38 are considered to be “safe”. According to political website 270toWin’s polls, the Republicans are currently ahead. It is there-fore quite possible that the Republicans will gain seats and increase their influence in the Senate. Who will be in charge in the House of Representatives will probably depend on the outcome of the election.

Trump would be less restricted than Biden in the event of an election victory. While Biden would (probably) face a blockade in the event of a victory, Trump could (probably) work with a majority in Congress.

What is unlikely to change under either president

Regardless of who moves into the White House, protectionism, anti-China policies, rearmament, and high national debt are likely to continue.

1. Protectionism

Anyone hoping for a little less “America first” and a little more trade openness from Joe Biden has been proven wrong in recent years. Biden is said to be pursuing a policy of “polite protectionism”: he posts fewer angry tweets than his predecessor, but still has America’s interests firmly in mind. Many of Trump’s national security tariffs or voluntary restrictions that were negotiated with other countries remained intact under Biden. Biden appears to share Trump’s view that protecting the US steel industry is a matter of national security. Other measures can also be seen as protectionist. One example is the Chips and Science Act promoted by Biden, which provides billions in investment in semiconductor manufacturing, research, and development and is intended to create more domestic jobs in the manufacturing industry.

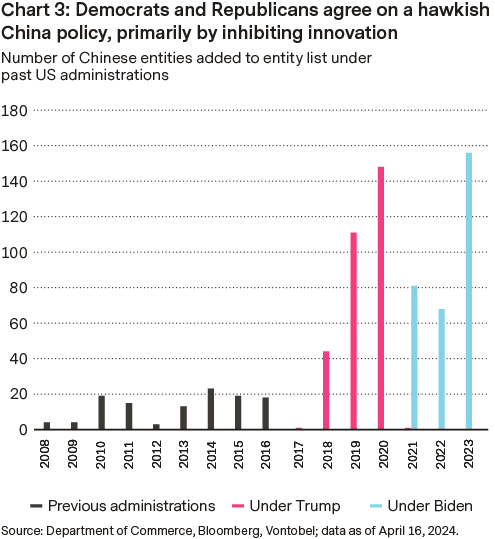

2. Anti-China policy

The attitude towards the world’s second-largest economy is also unlikely to change much. Both Republicans and Democrats have learned over the years that an anti-China policy increases voter favorability. While Trump is openly hostile to China (like his various punitive tariffs imposed by Trump or Trump’s statement that Covid-19 is a “Chinese virus”), Biden’s approach is more subtle but no less determined. This becomes clear, for example, when taking a look at the Chinese companies that have been placed on the “entity list” by the US in recent years (see chart 3).

3. Rearmament

Another point is the trend towards military rearmament. Trump has repeatedly called for higher military spending and has also demanded this from other NATO member states. In February, he even announced that he would not stand by NATO allies

in an emergency. Biden also advocates for increased spending—he submitted a budget proposal in March 2024 for fiscal year 2025 that includes a request for USD 850 billion in discretionary funding for the Department of Defense (+ 4.1 percent over fiscal year 2023).

4. Debt issue

The debt issue (and associated questions around the “sustainability” of debt) is also likely to persist. At first glance, ever-increasing government debt is nothing new. Government debt, measured as a percentage of gross domestic product (GDP), has only been heading in one direction for years: upwards. In the 1980s, the national debt was still around 30 percent; now it is over 120 percent. What could soon become a problem, however, is the higher cost of servicing the debt (due to higher interest rates). These are higher than they have been for 40 years.

Trump’s campaign promises

Summarizing all of Trump’s campaign promises is quite ambitious. Here are the five most important areas: Fiscal policy, monetary policy, trade policy, immigration policy, foreign policy.

1. Fiscal policy

Trump’s fiscal policy agenda is primarily aimed at lowering taxes. During his first term in office, he had already attempted to reduce corporate tax from 35 percent to 15 percent. In the end, it was at 21 percent. Trump and his advisers have discussed further cuts to corporate tax rates, potentially as low as 15 percent, according to a September article by the Washington Post. Private individuals could also hope for lower taxes under Trump. In the past, lower taxes have weakened budgetary discipline in the US. It can be assumed that the already high budget deficit will continue to grow.

Trump wants to make savings elsewhere and, among other things, discontinue state funding for public broadcasting. Foreign aid, climate subsidies, and investments in sustainable technologies are also to be cut back (Trump sees the expansion of electric cars, for example, as paving the way for mass redundancies in the US car industry).

2. Monetary policy

Trump has primarily zeroed in on Fed Chair Jerome Powell. Trump and Powell share a turbulent history. Trump appointed Powell (who is also a Republican) as Fed Chair in 2017 and praised him at the time as “wise” and experienced. But when Powell raised interest rates in 2018, he fell out of favor. Trump described Powell and the Fed as “clueless” and called for Powell’s dismissal. In 2019, Trump even tweeted the question of “who is our bigger enemy” Powell or China’s President Xi Jinping. In 2024, Trump hinted that Powell would lower interest rates to help the Democrats and secure Biden’s second term in office.

Powell’s dismissal is likely to be difficult. Legally speaking, the President can only remove a Fed Board member (including Powell) for “cause”. Dissatisfaction with the Fed’s monetary policy is unlikely to be a valid point.

However, Trump has already announced that if he were to be elected President, he wouldn’t give Powell a second term in office (Powell’s four-year term expires in 2026). After that, he could try to appoint a Fed chair he prefers, though Congress would have to give its approval.

3. Trade policy

Trump continues to strive for an “America first” policy. In the event of a second Trump term in office, greater trade policy uncertainty can therefore be expected. He has already announced that he would impose import tariffs of 60 percent on goods from China and 10 percent on goods from other countries if he wins the election. The current average tariff rate is 3 percent, or 19 percent in the case of China, according to the South China Morning Post. If Trump were to push this through, the European Union—as the US’s second-largest trading partner—would be particularly affected, alongside China.

Restricting Chinese ownership of US infrastructure (e.g., in the areas of energy, technology, telecommunications, and natural resources) is also under discussion. Trump is also considering a ban on investments by US companies in China and a rethink of the US’s role in important organizations such as the WTO.

4. Immigration policy

Trump’s plans for immigration sound similarly determined. At a recent fundraiser, Trump complained that no people from “nice” countries (Trump’s definition: Denmark, Switzerland, and Norway) were immigrating to the US. Instead, he said, we have to contend with people from other countries. But legal immigration and the right to citizenship for babies born in America should also be put to the test.

Although stricter immigration policy would be welcomed by populist voters, it could have negative consequences for the labor market.

Strong immigration under Biden has had a relaxing effect on the tight labor market. The latter has been struggling for some time with too high a demand for labor and too low a supply of labor. Lower immigration would exacerbate the shortage of labor and further fuel wage pressure (and thus inflation).

5. Foreign policy

Apart from China policy, relations with Russia are also likely to be one to watch. Trump appears to have a good relationship with Russian President Vladimir Putin. While Trump’s statement that he would settle the Ukraine war within 24 hours may be a bit ambitious, one way he could influence the war would be by cutting off financial aid to Ukraine, which is what Hungarian Prime Minister Viktor Orban claims Trump told him in a meeting in March. That would, however, require convincing a Russia-sceptic Congress.

A “forced” settlement of the war would not necessarily be market-relevant: while oil prices rose significantly after Russia’s invasion, they have fallen since the end of 2022, i.e., the “geopolitical risk premium” of the Russia-Ukraine war is no longer really present. Instead, other conflicts (Israel-Hamas) are driving the oil price.

Trump’s Iran policy could have more of an impact on the oil price. For Trump, sanctions seem to be the only way to prevent Iran from enriching uranium (and thus from making a nuclear bomb) in the future. Iran is one of the largest oil producers in the world and ranked 7th in 2016 with a production of 4.4 million barrels per day. After Trump’s surprising withdrawal from the Joint Comprehensive Plan of Action (JCPOA) nuclear deal in May 2018, the price of oil rose by 60 percent within a short period of time.

According to estimates, 2 to 4 million barrels of oil disappeared (at least temporarily) from the world market.

In the rest of the Middle East, Trump impressed with his diplomatic skills. The Abraham Accords (2020), brokered by his administration, normalized diplomatic relations between Israel and some Arab states. The signatories—the United Arab Emirates (UAE), Bahrain, and Israel—reaffirmed their desire to strengthen peace in the Middle East. The UAE and Israel also concluded a peace agreement. Trump also maintains good relations with Saudi Arabia and the important gas exporter Qatar.

What Trump 2.0 could mean for the economy

It is not easy to say how a second Trump term would affect key macroeconomic variables. Firstly, it is not clear whether Trump can win a majority in Congress. Secondly, it is not certain whether the Republicans will go along with all his proposals. This will influence whether (and how) his campaign promises are implemented. Thirdly, the current situation is different: many of Trump’s campaign promises would be met with a much tighter labor market today. In other words, the upside risks for inflation are higher than they were during Trump’s first term in office. These are possible scenarios:

1. Growth

A second Trump term might be broadly positive for economic growth. The tax cuts planned by Trump should lead to a higher fiscal deficit. This would result in a positive fiscal stimulus. Trump’s deregulation plans could also lead to higher productivity. As long as Congress goes along with Trump, this should support the US economy.

In the longer term, however, there would also be negative implications for growth. Lower immigration would probably lead to weaker population growth. Due to increased trade uncertainty, there is also a risk that companies will invest less. Higher tariffs and the associated higher prices could also lead to lower consumption.

2. Inflation

A second Trump term is likely to be largely reflationary, i.e., the price level in the US is more likely to rebound amid a stronger economy and private consumption. This is partly due to the presumably higher fiscal deficit and the associated positive demand stimulus, and partly due to lower immigration and the associated risk of an additional shortage on the labor market (higher wage pressure due to lower labor supply). Last but not least, higher tariffs are also likely to be reflected in higher inflation.

A small disinflationary effect could come from lower immigration (fewer immigrants, less demand for housing, and thus less pressure on house and rent inflation).

3. Interest rates

Between 2017 and 2018 (i.e., during Trump’s first term in office, when he had full control of Congress), interest rates (in this case, bond yields) rose. Even if Trump wins another election, interest rates are likely to rise due to higher economic growth, higher inflation, and the prospect of a Republican-controlled Congress. However, trade uncertainty and foreign policy geared towards maximum pressure could somewhat limit the upside potential.

4. US dollar

The combination of stronger economic growth, higher inflation, and trade uncertainty harbors upside risks for the US dollar. However, the Fed’s reaction function is crucial here. The prerequisite for a stronger dollar is that the central bank takes decisive action against higher inflation (i.e., raises interest rates). If it does not do this and stands idly by and watches inflation rise, this is more likely to weigh on the dollar.

What Trump 2.0 would mean for financial markets

It’s important to remember that asset classes are also influenced by other factors, such as the global economic cycle, which in turn is influenced by far more than just the outcome of the election.

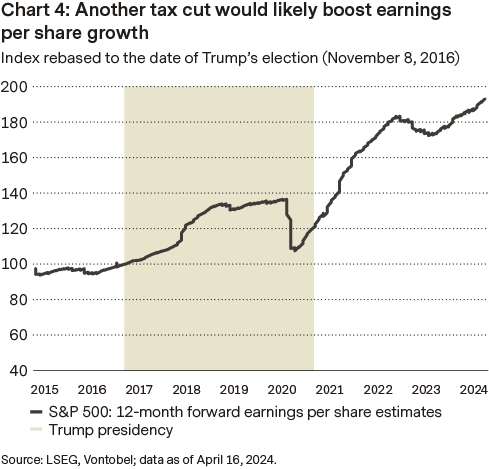

1. Equities

If history is any guide, equity markets often trend sideways in the run-up to elections. This is hardly surprising: election campaigns are typically accompanied by un-certainty about the future political course, and stock investors don’t like uncertainty. Once a winner was determined, the markets usually went up—even if the incumbent president was not re-elected. A further tax cut would probably have a positive impact on earnings per share (see chart 4). At the same time, investors should be prepared for higher equity market volatility (similar to 2019), due to the more unpredictable policy. Within the asset class, developed-market equities are poised to benefit the most. There could be headwinds for some emerging-market stocks due to the trade war.

2. Bonds

Bonds are likely to struggle more in the event of a second Trump term. While the asset class would benefit from a stronger US dollar, the combination of higher growth, higher inflation, and higher interest rates would have a negative impact. A stronger economy makes equities look more attractive than bonds from an investor’s perspective. Higher inflation reduces the purchasing power of a bond’s future cash flows. Rising interest rates cause existing bonds to lose value.

3. Alternative investments

If a reflationary second Trump term is confirmed, commodities could also benefit. Higher economic

growth should also benefit the cyclical asset class. While gold could benefit temporarily from increased geopolitical uncertainty, higher interest rates and a stronger US dollar are likely to weigh on the precious metal (real interest rates and the US dollar generally move in the opposite direction to gold).

Wirtschaftstrends ändern und Jahr der Anleihen lässt sich Zeit

Für 2024 hatten die Anleger anfänglich mit weniger Wachstum weniger Inflation sowie baldigen, deutlichen Leitzins-Senkungen gerechnet. Doch nun entpuppt sich das Wachstum als stet und der Inflationsdruck als hartnäckig, während sich die Normalisierung der Geldpolitik verzögert und in milderen Schritten erfolgen dürfte. Das erhoffte Jahr der Anleihen lässt auf sich warten.

Grosse Teile der US-Wirtschaft präsentieren sich trotz der aggressiven geldpolitischen Straffung nach wie vor robust. Nachdem eine unmittelbare Rezession ausblieb, rechneten die Anleger mit hartnäckiger Inflation. Das Multi Asset Team war skeptisch, dass diese so schnell sinken würde, wie im Markt vor nicht allzu langer Zeit eingepreist – denn sie war der Meinung, die letzte Phase im Kampf gegen die Inflation sei die schwierigste.

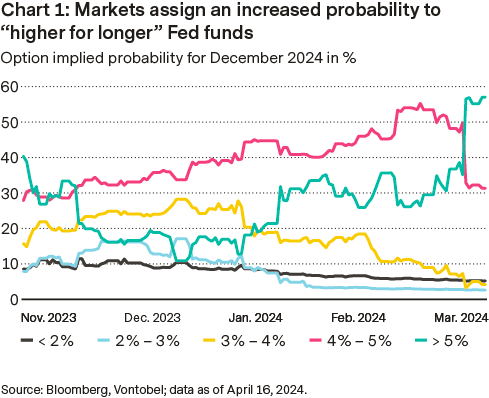

Vieles hängt von den Daten der nächsten Monate ab, und auch davon, wann die US-Notenbank Fed ihren Leitzins senken wird und in wie vielen Schritten bis Ende Jahr. Die meisten Fed-Vertreter gehen von zwei oder drei Zinssenkungen für 2024 aus. Doch die Situation könnte sich deutlich ändern, wenn die Inflation noch länger nicht abflaut, die Inflationserwartungen ausser Kontrolle geraten oder der Arbeitsmarkt sich unerwartet abschwächt. Was sich bei den Marktpreisen deutlich geändert hat, ist das Ausmass der Zinssenkungen. Anfang des Jahres preiste der Markt eine Wahrscheinlichkeit von 10 Prozent ein, dass der US-Leitzins Ende Jahr bei 2 Prozent oder darunter liegen würde. Inzwischen ist diese Wahrscheinlichkeit gesunken. Die Anleger scheinen von einer freundlichen Wirtschaftsentwicklung auszugehen. Optionen preisen derzeit eine Wahrscheinlichkeit von 30 Prozent ein, dass der US-Leitzins Ende Jahr zwischen 4 Prozent und 5 Prozent liegen wird, wobei wahrscheinlicher ist, dass sie über 5 Prozent liegen wird.

Credit caution

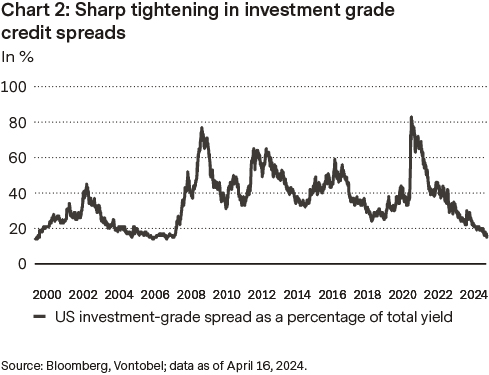

Option-adjusted spreads to US Treasuries, which reflect the difference in yield between sovereign and corporate bonds, are a common gauge of default risk. The sharp tightening in investment-grade credit spreads has considerably reduced the margin for safety in credit. Spreads now represent less than 20 percent of the total yield of the Bloomberg US Corporate Bond Index (see chart 2).

This “price to perfection” encourages more vigilance in this segment. High-yield risk premia ticked up to 329 basis points after dropping below 300 basis points over the past month, the tightest level in about three years. High-yield bonds could come under pressure in this very uncertain environment. Expectations of higher default rates, paired with fairly restrictive monetary policy, are expected to weigh on this segment. The current valuation of US high-yield spreads implies only very modest default rates and the absence of a near-term slowdown.

Can earnings keep stocks rolling?

After almost five consecutive months of stellar performance, equity markets have been in a broad-based consolidation phase since the end of March. Stock investors are beleaguered with questions. Can the current earnings season keep stocks rolling? Can economic growth withstand higher yields and defy the Fed’s extending its “higher for longer, no urgency to cut rates” mantra as it’s still dissatisfied with the progress made in taming inflation?

Since October, valuation re-rating has been the biggest driver behind stock markets’ performance, reflecting an anticipation for good news, ranging from less restrictive monetary policy to the prospect of a soft landing.

The result? In the US, the S&P 500 Index closed above its 50-day moving average (the average closing price over the last 50 trading days) for more than 160 consecutive days, the longest streak since the global financial crisis. This phenomenon occurred only on rare occasions since 1945. But three consecutive hotter-than-expected monthly prints for US consumer price inflation, stronger-than-anticipated US consumer spending data, and rising tensions in Eastern Europe and the Middle East, which caused energy prices to spike, were enough to rekindle inflation fears.

The Fed’s “higher for longer” narrative and hawkish stance drove up yields and recalibrated market expectations that rate cuts were just around the corner. Markets were pricing in up to seven rate cuts this year at the start of the year, beginning as early as March. At the time of this writing, expectations have shifted to less than two, starting in the third quarter at the earliest. Is the world back to the same central-bank plot as last summer, and is this the beginning of a stronger correction? Probably not. First, given the backdrop of higher inflation and the pushback on a pivot, coupled with extremely bullish investor sentiment at the end of March, a consolidation is certainly not surprising. Statistically, there have been three to four pullbacks, on average, of about 5 percent or more per year since 1920. Second, for central banks, the major difference from last year is that the heavy lifting has been done as economic growth is recovering globally. This suggests the nearing of the beginning of a new economic cycle. If so, the reporting season that recently kicked off could show a continuation of earnings surprises seen in the last quarters (see chart 1), which in turn would be supportive of equities.

Crude climbs, gold glitters

The Israel-Hamas conflict has dominated the headlines since October 2023. At the time, the Mutli Asset team outlined three possible scenarios: a scenario in which the conflict remains limited to Israel and Hamas, a scenario in which Hezbollah becomes involved, and a scenario in which the “shadow war” fought between Israel and Iran escalates into a more direct conflict. The third scenario became reality in mid-April, when Iran sent drones and missiles towards Israel in response to an Israeli attack on its consulate in Syria earlier that month (for which Israel has not taken official responsibility).

The attack marked a new, serious phase in the conflict and temporarily pushed oil above 90 US dollars per barrel (see chart 1). Going forward, a lot depends on how the conflict develops. If there is no further escalation, the focus will sooner or later return to the most important drivers (supply, demand, etc.). However, the potentially higher geopolitical attention of the markets in general could remain. In the event of a further escalation, higher oil prices (even an oil price shock) could be expected. Should a shock occur, the Organization of the Petroleum Exporting Organization of the Petroleum Exporting Countries and its allies (OPEC+) could rush to the rescue, as they have around 5 million barrels per day of spare pro duction capacity.

Many stakeholders are trying to de-escalate the situation. While US President Joe Biden assured Israel’s Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu of his support, he also warned against retaliation by Israel. In the event of an Israeli retaliatory strike, the US would more than likely not participate. The Saudi Foreign Minis try also expressed great concern about the military escalation in the region and called on all parties involved to exercise the utmost restraint.

Gold’s latest surge can’t be explained by geopolitics alone. The yellow metal chased one high after the next despite rising US real yields and US dollar strength (usually headwinds for gold). An often-used explanation is strong central bank demand in emerging markets (China and India added gold at a healthy clip).

There may be another, lesser-heard explanation, which is that the market knows something investors don’t. When you look at the recent performance of gold and Bitcoin, you can’t help but notice that they are “joined at the hip”, i.e., a 1 percent move in gold equates to a roughly 5 percent move in Bitcoin. This is surprising, as both are usually seen as “competitors”. One could argue that markets are increasingly concerned about the huge amount of liquidity in the system (see chart 2), and flock to alternative stores of value.

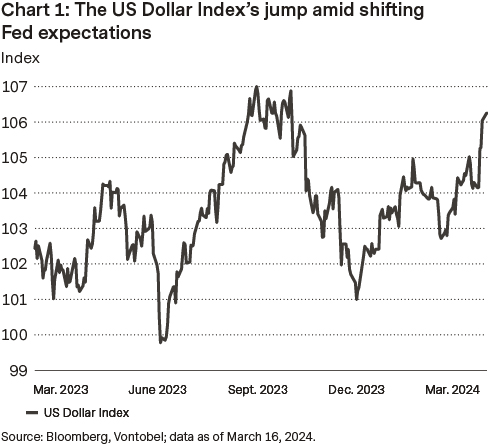

Ditched interest rate cuts boost US dollar

US dollar bears have experienced a frustrating start to 2024. So far this year, the US Dollar Index has climbed about 5 percent (see chart 1), buoyed by market expectations that have shifted from anticipating up to seven rate cuts for 2024 by the Fed to fewer than two. A fresh bout of risk aversion is also filtering through markets, compounding the US dollar’s advance.

Given its currently high level, the potential for further gains by the US dollar is likely limited. Should upcoming data and communications suggest that the Fed will only delay its initial rate cut by a few months, yet still implement several rate reductions this year and next dollar bears might soon take the upper hand again.

However, if indications from the Fed suggest that rate cuts may not happen this year, or further tightening is still required, it would likely mean the recent dollar rally will continue. These developments would underscore the dol lar’s strengthening trend in response to the Fed’s monetary policy signals.

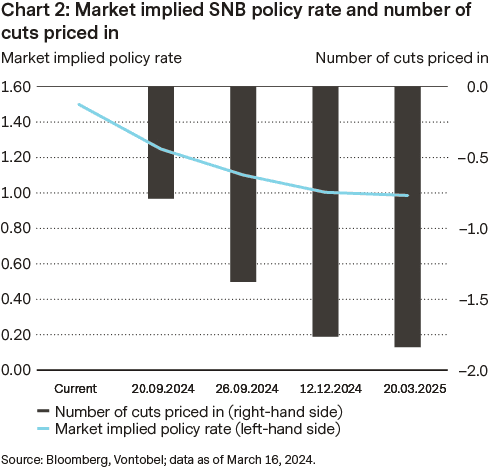

Short-lived geopolitical boost to the Swiss franc

Although a fresh wave of geopolitical tensions provided some support to the Swiss franc, the underlying funda mentals remain unchanged: the Swiss National Bank (SNB) is confronted with significant dovish risk, indicating potential further downside for the franc. Despite weaker consumer price inflation data in Switzer land, markets continue to anticipate a limited SNB cutting cycle, with only two more cuts fully priced in for this year, ultimately reducing the policy rate to 1 percent (see chart 2). Swiss inflation showed an unexpected slowdown, reinforcing the decision of the SNB to cut interest rates last month. The SNB surprised investors by lowering its key rate last month, a move that was the first of its kind among G-10 central banks since the global inflationary spike.

In March, Swiss consumer prices increased by just 1 per cent year-over-year, marking the lowest increase in two and a half years, contrary to the 1.3 percent rise economists had forecasted. The drop in inflation was broad based, indicating that inflationary pressures are subsiding more rapidly than anticipated in Switzerland. The departing SNB President Thomas Jordan expressed confidence that there is “very little risk” of inflation climbing beyond the 2 percent upper limit of the central bank’s target. The SNB had previously anticipated a modest acceleration in inflation during the second and third quarter, primarily driven by expected increases in rent.

Authors

Frank Häusler, Chief Investment Strategist

Stefan Eppenberger, Head Multi Asset Strategy

Christopher Koslowski, Senior Fixed Income & FX Strategist

Mario Montagnani, Senior Investment Strategist

Michaela Huber, Cross-Asset Strategist

Risks

Disclaimer:

This information is neither an investment advice nor an investment or investment strategy recommendation, but advertisement. The complete information on the trading products (securities) mentioned herein, in particular the structure and risks associated with an investment, are described in the base prospectus, together with any supplements, as well as the final terms. The base prospectus and final terms constitute the solely binding sales documents for the securities and are available under the product links. It is recommended that potential investors read these documents before making any investment decision. The documents and the key information document are published on the website of the issuer, Vontobel Financial Products GmbH, Bockenheimer Landstrasse 24, 60323 Frankfurt am Main, Germany, on prospectus.vontobel.com and are available from the issuer free of charge. The approval of the prospectus should not be understood as an endorsement of the securities. The securities are products that are not simple and may be difficult to understand. This information includes or relates to figures of past performance. Past performance is not a reliable indicator of future performance.

© Bank Vontobel Europe AG and/or its affiliates. All rights reserved.