Investors’ Outlook: Turning the page

While trade tensions between the US and China eased and the shutdown was eventually ended, uncertainty remains regarding the future of technology companies and digital currencies. The question remains: How sustainable are the current boom cycles in AI, and what global power shifts could shape the coming years? A look at geopolitical and economic developments shows that the world order is increasingly shifting towards multipolarity – with consequences for investors and markets worldwide.

Eine volatile Passage für die Märkte

November brought volatility, as improving trade relations and the end of the longest government shutdown in US history coincided with wavering sentiment toward AI and cryptocurrencies.

Trade tensions eased as both the US and China made con-cessions, and the US reduced tariffs on more than 200 food and beverage products. It also reached a preliminary agreement to lower levies on Switzerland. These moves signaled potentially fewer disruptions to global commerce ahead. Polls indicated that affordability concerns weighed on US President Donald Trump’s approval ratings and harmed Republican candidates in recent elections.

The 43-day US government shutdown ended with a funding package that will keep the government running until January 30. During the closure, statistical agencies halted activity, delaying several September releases and preventing the collection of October data. With operations now restored, markets can expect a flurry of new data in the coming weeks, though investors may question how reliable it is. These developments were partially overshadowed by market volatility amid growing investor skepticism of AI-related stocks, fearing the rally may be approaching bubble territory. Cryptocurrencies experienced a USD 1 trillion selloff.

Monetary policy will likely remain supportive next year and political leaders will likely adopt a pro-growth stance and work to reduce policy uncertainty. As investors debate whether or not the Fed will cut interest rates in December, the Multi Asset team is more focused on whether policymakers signal a sustained commitment to rate cuts going forward. The team also anticipates a broader effort to mitigate uncertainty as the US approaches midterm elections - signs of which are already visible in Trump’s rollback of food tariffs, his more conciliatory tone toward trading partners like China and Switzerland, and his rare acknowledgment of declining approval ratings.

Multipolarity - The new world order

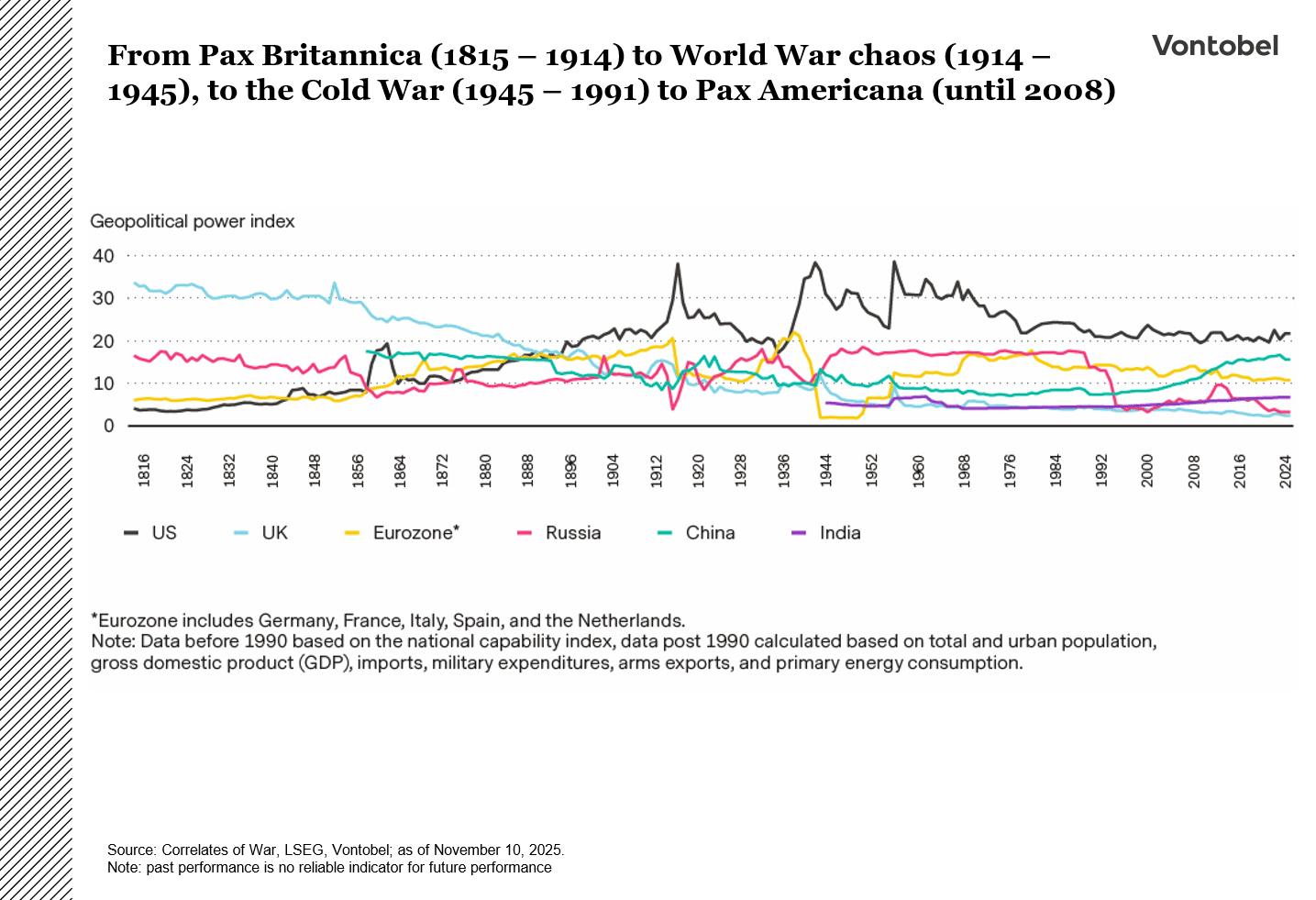

For centuries, global order has been shaped by the rise and fall of great powers, driven by economic dominance, industrial revolutions, and shifting geopolitical alliances. The 19th century was defined by Pax Britannica (1815 – 1914), a period of relative stability under British naval and economic supremacy, powered by the Industrial Revolution and colonial expansion. That order unraveled in the early 20th century, as the chaos of two world wars upended borders, economies, and alliances. The post-war era gave way to the Cold War (1947 – 1991), a world dominated by the ideological and military rivalry between the US and the Soviet Union.

With the fall of the Berlin Wall, the US emerged as the unchallenged global hegemon, ushering in Pax Americana, a period of US-led globalization and economic integration.

Since the early 2000s, however, Pax Americana has shown signs of strain. On the trade side, one of the first major shifts occurred in 2001, when China joined the World Trade Organization, accelerating its rise as a global economic powerhouse and challenging US dominance in global commerce. China’s Belt and Road Initiative, launched in 2013, expanded its economic and geopolitical reach by financing infrastructure projects, particularly in emerging markets.

The gradual erosion of Pax Americana is visible in concrete data. China has become the world’s second-largest economy, its size now comparable to that of the entire European Union. The US remains the world’s largest economy, but its dominance has diminished in key areas. Its share of the global manufacturing value chain declined from 25 percent in 2000 to 17 percent in 2023, and its portion of worldwide military spending fell from 53 percent in 2000 to approximately 43 percent over the same period.

On the sentiment side, the 2008 financial crisis exposed vulnerabilities in the US-led system, shaking international confidence in the American economic model and prompting many governments to diversify their economic partnerships. The election of Donald Trump in 2016, and again in 2024, marked another turning point, as his “America First” policies and withdrawal from multilateral agreements signaled a retreat from the stabilizing role the US had long played in global affairs.

A recent Ipsos survey of 29 countries, conducted in April 2025, showed the decline in the US’s global standing. When asked whether the US would have a positive influence on world affairs, only 46 percent agreed—a sharp drop from the 59 percent recorded in September / October 2024, just before Trump’s re-election. The reputational damage is especially pronounced in countries long considered close US allies. For instance, in neighboring Canada, the share of respondents expressing a favorable view of the US plunged from 52 percent to just 19 percent.

There are also signs that Americans themselves may be growing weary of the country’s long-standing role as the “world’s police”. Findings from the World Values Survey, conducted between 2017 and 2022, revealed a significant generational divide over military engagement. Asked whether they would be willing to fight for their country in a war, only 41 percent of Americans aged 15 to 24 said yes. This stands in sharp contrast to the 72 percent of those aged 55 to 64 who expressed a willingness to serve.

It also diverges from the 91-country average, which showed 68.5 percent of the younger respondents and 64 percent of the older ones were willing to fight. In China, willingness was higher still, with around 90 percent of respondents across all age groups saying they would be ready to serve.

This turn invites a critical question: what will the new world order look like in the years to come?

Understanding unipolarity, bipolarity, and multipolarity in global power dynamics

The concepts of unipolarity, bipolarity, and multipolarity help explain these shifts in global power dynamics. Unipolarity describes a world dominated by a single superpower, as seen during the Pax Americana era. Bipolarity refers to a system where two dominant powers or blocs compete for influence, such as during the Cold War between the US and the Soviet Union. Multipolarity, by contrast, is characterized by power distributed among multiple influential states or blocs, creating a more fragmented and competitive global environment.

Why multipolarity, not bipolarity?

For some, the escalating rivalry between the US and China has revived memories of the ideological standoff of the Cold War, stirring fears of a potential return to a bipolar world order. However, the new global landscape is probably more accurately described as a multipolar world order.

Why? First, the Multi Asset team believes neither China nor the US is truly ready for a bipolar world. In China’s case, this is particularly noticeable when comparing the economic and military weight of the putative Chinese camp (China, Russia, and Iran) with that of the Western camp (the US, EU, UK, Canada, Australia, Japan, and South Korea). Measured by share of global GDP, the Chinese camp accounted for some 19 percent in 2024, compared to the Western camp, which held about 56 percent. The logical conclusion for China’s export-heavy economy? It needs markets beyond its own “alliance.” A similar observation can be made in military spending as a percentage of global spending. The Western camp accounts for around 57 percent of global military spending, compared with just about 18 percent for the Chinese camp.

For the US, the Multi Asset team believes that, unlike during the Cold War, it has a vested interest in maintaining trade relations with China. This is particularly evident in China’s near-monopoly over the rare earths market, essential for producing components like magnets, catalysts, and phosphors used across renewable energy technologies, electronics, and defense industries. China is estimated to possess half of the world’s rare earth reserves, while producing 69 percent of global mined supply and 92 percent of rare earth refining. It also dominates magnet production, accounting for an astonishing 98 percent of global output.

Apart from questions around readiness, the US does not appear to be behaving as if it wants to establish a bipolar world. Washington has imposed numerous tariffs on a wide range of countries, regardless of whether they could serve as (potential) allies against China.

What also argues for a multipolar world order is that European allies, for example, take a slightly different view on whether China poses a military security threat. While more than 60 percent of US respondents see China as a major threat to their domestic security, only 7 percent of Germans share that view. In fact, 51 per-cent of German respondents said they do not regard China as a military threat at all.

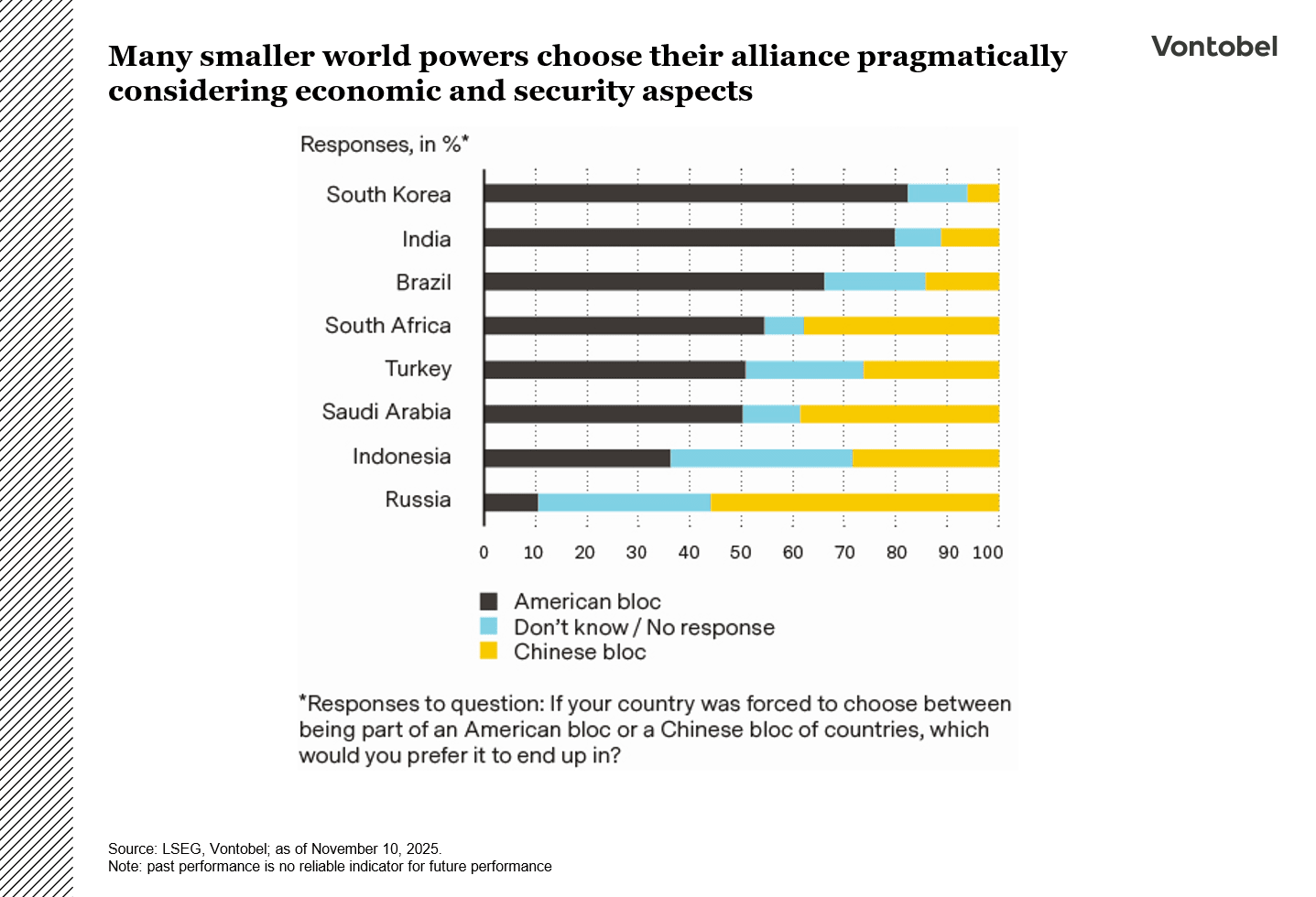

Today’s multipolar world order comes to the fore when examining the perspectives of regional powers. When asked which bloc their country should align with if forced to choose between an American or a Chinese camp, more than 35 percent of Indonesian respondents and over 33 percent of Russian respondents said they were undecided. In Saudi Arabia, around half of the respondents favored the American bloc, while 38 percent preferred alignment with China. This suggests that, rather than blindly adhering to ideology, many countries choose their alliances pragmatically, prioritizing economic and security interests. Another example of this occurred in May 2022, when the United Nations voted on a resolution condemning Russia’s invasion of Ukraine. A majority backed the measure, but a notable 34 countries, including influential actors such as India, Vietnam, and South Africa, abstained, and six voted against it.

Security consequences of the new world order

The emergence of a new multipolar world order carries security implications on both global and national scales. Globally, the absence of a single dominant power capable of enforcing stability has coincided with an increase in the number of conflicts. According to the Uppsala Conflict Data Program, the number of interstate and internationalized internal conflicts has risen from single digits during the early years of Pax Americana to more than 50 conflicts since 1911.

However, the increasing number of conflicts does not have to imply that World War III is imminent. Instead of large-scale world wars, the proliferation of nuclear weapons—estimated at 4,309 warheads for Russia, 3,700 for the US, and 600 for China—has shifted the nature of conflict toward proxy wars, where major powers compete indirectly through regional allies, further exacerbating instability in fragile states.

At the national level, countries, particularly in Europe, face rising security costs as they are forced to bolster their defense capabilities in response to growing threats and reduced US security guarantees. According to data from the Stockholm International Peace Research Institute, every NATO member except the US has increased military spending as a percentage of GDP over the past decade. The pressure to increase defense is expected to continue.

Asian countries are also likely to face higher security costs in the future. For decades, the US has maintained a strong presence in the Middle East through a network of air and naval bases, providing security guarantees in the region. But shifting security priorities and evolving relationships with host nations have led to changes in the locations and operational needs of US forces. This realignment is particularly significant as most Middle Eastern oil now flows to Asia, with China and India the largest single-country recipients.

Lastly, Taiwan has emerged as a new tail risk to watch. China’s claim to the island is not new. Although Taiwan has functioned as a self-governed democracy since 1949, China continues to consider it part of its territory under the “One China” policy. But tensions have escalated in recent years, partly fueled by the intensifying race for technological dominance in the semiconductor industry. Taiwan plays a critical role in global semiconductor production, accounting for over 60 percent of the world’s semiconductor manufacturing and more than 90 percent of the most advanced chips.

The Multi Asset Boutique believes there is a growing risk that China may eventually seek to seize Taiwan, and the stronger it becomes, the greater the likelihood of such an action (a scenario that would have been much less conceivable in a unipolar world). For now, China is still too weak and isolated to act decisively. However, the longer China waits, the more the Taiwanese population distances itself from identifying as Chinese. According to Chengchi University’s Election Study Center, more than 62 percent of participants identified as Taiwanese in 2025, up from just 17 percent to 20 percent in the early 1990s. Over the same period, the share identifying as Chinese fell from 25 percent to just 2.3 percent. Taiwan’s shift away from China is also reflected in its trade data. In 2021, China accounted for 30 percent of Taiwan’s exports. By late 2025, this figure had dropped to 16 percent. Meanwhile, Taiwan’s exports to the US increased from 15 percent in 2021 to more than 27 percent.

Economic consequences of the new world order

The economic consequences of the new multipolar world vary depending on one’s perspective. Optimists argue that global power competition could boost investments as countries embark on their own “race to the moon,” that greater diversification will reduce dependence on any single dominant economy, and that foreign policy should be viewed realistically—there are no permanent friends or enemies, only national interests.

Pessimists, on the other hand, contend that heightened policy uncertainty of a multipolar world will cause businesses and consumers to delay decisions, that increased trade restrictions will hinder growth, and that global supply chains will become more vulnerable in the absence of a single global hegemon. They also warn of a growing number of conflicts, including proxy wars.

The winning candidates of the new world order

There are three types of countries that are likely to benefit in a multipolar world, according to the Multi Asset team.

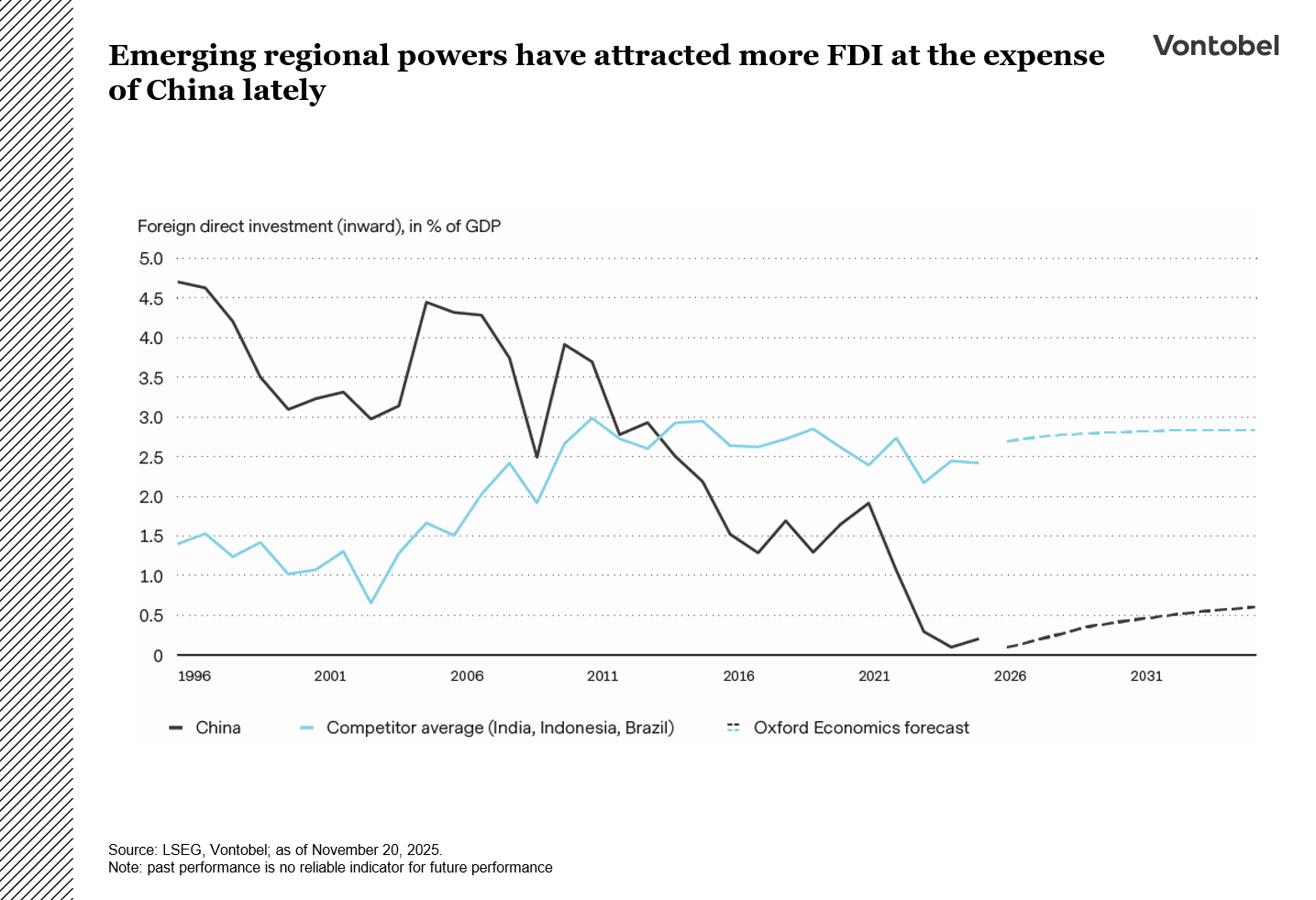

Emerging regional powers. A multipolar world often intensifies competition among major powers for influence, trade partnerships, and investment opportuni-ties. Emerging economies can capitalize on this rivalry to negotiate better trade deals, attract foreign direct investment (FDI), and gain access to advanced technologies. Examples include India, Brazil, and Indonesia.

Resource-rich nations

Countries with abundant natural resources gain strategic importance as multiple powers compete for access. This competition can result in higher revenues and more favorable terms for resource-exporting nations. Examples include Saudi Arabia, the United Arab Emirates, and Chile.

Emerging manufacturing hubs

Countries that diversify their trade relationships and reduce dependence on any single dominant power, such as the US or China, can achieve more balanced economic growth. Low-cost countries may also have an opportunity to increase their share of global manufacturing as the great powers remain preoccupied with competing against one another. Examples include Vietnam, Bangladesh, and Poland. That said, countries hoping to leverage these potential opportunities must first do their “homework,” namely strengthening domestic frameworks, addressing systemic issues, and fostering sustainable development. Only by doing so can they position themselves as reliable and capable players on the global stage.

Reading between the lines

The US government shutdown has knocked key data off the calendar, from jobs to growth figures, just as investors are trying to judge how late they are in the cycle. With the usual signposts missing, markets trade on headlines and central bank speeches instead of hard numbers, and volatility can rise even when fundamentals have not changed much.

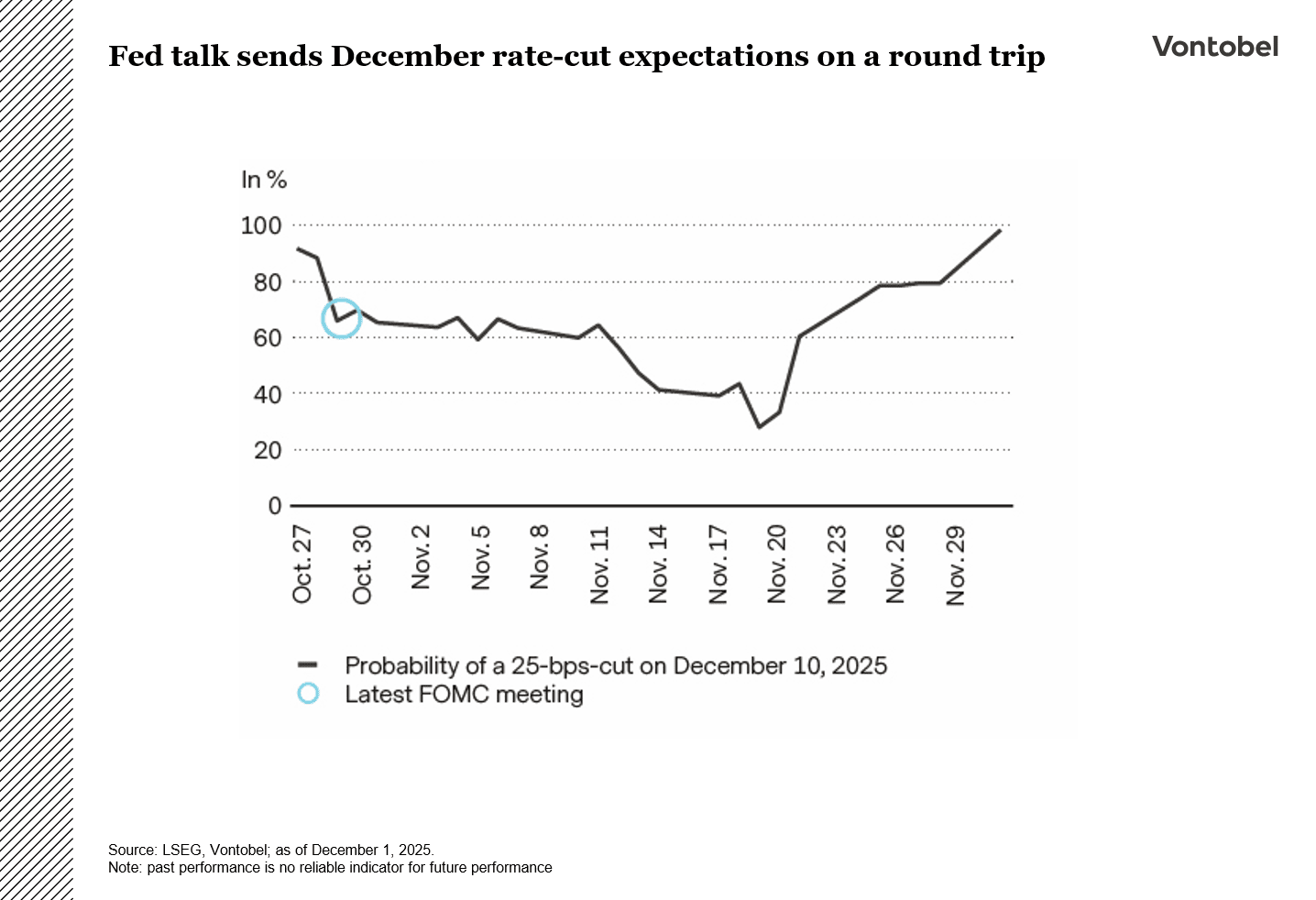

In that context, it makes sense to look closely at how the Fed is priced. Markets had initially scaled back expectations for a third consecutive rate cut after hawkish Fed officials warned that inflation is still too high. The implied probability of another quarter-point move dropped from nearly 70 percent to about 30 percent. However, that pic-ture has shifted again. A series of more dovish comments from key Fed officials, who have pointed to softer labor-market data, has pushed those odds back up. Traders have effectively completed a round trip. Whether the Fed cuts again in December or not, Chair Jerome Powell faces the challenge of holding a fractured committee together with limited data to guide him.

The bond market meets the AI super-cycle

Since September, Oracle, Microsoft, Meta, Alphabet and Amazon have sold about USD 88 billion in AI- and cloud-linked bonds. Oracle raised USD 18 billion in September, Meta issued USD 30 billion in its biggest deal yet, with maturities from 5 to 40 years, Alphabet sold USD 25 billion in early November, and Amazon followed with USD 15 billion. Meta also helped arrange a USD 27 billion private-debt package for the Hyperion AI data-center campus, financed mainly by private credit and bond funds through a joint venture. That keeps leverage off Meta’s balance sheet but tells the same story: AI infrastructure is increas-ingly funded with long-dated debt rather than just retained earnings or equity.

These companies are not issuing because they lack cash. AI demands huge, front-loaded spending on data centers, power, networks and graphics processing units, and long-maturity bonds are a natural match for those long-lived assets. With strong balance sheets and low net leverage, adding investment-grade (IG) debt can lower funding costs, preserve cash buffers, and still leave room for buybacks and dividends.

For credit investors, this means a surge in long-dated, AI-labelled supply from top-tier issuers. At the front end, the bonds still look like high-quality carry. Further out the curve, they are a long-term bet that the AI capex super-cycle will generate cash flows strong enough to justify locking in Big Tech risk for 30 to 40 years at tight spreads. In the end, these deals force bond investors to ask the same question as equity investors: how durable is the AI spending boom?

Under stress, but the binding holds

Concerns about a potential AI-driven bubble have inten-sified as questions grow over the monetization and funding of AI investments, with leverage coming more to the foreground.

By the beginning of November, many of the ingredients for a widely anticipated market consolidation were already in place: parts of the equity market had reached all-time highs, US valuations were near their richest levels in 15 years, and market breadth remained narrow. Technology and AI-related stocks, especially the largest US mega-caps, have dominated year-to-date performance, making a pullback a matter of “when,” not “if.”

The debate around an AI bubble became more heated, too. Visibility on revenue generation from this still-emerg-ing technology remains limited. The surge in AI-related capital expenditures (capex) and the diverse ways they are being funded, ranging from debt issuance and venture capital to more “creative” off-balance-sheet structures, has also begun to raise skepticism.

From a revenue standpoint, it is important to recognize that AI adoption is still in its early stages. Infrastructure investment is essential to unlock future growth, enter-prise and consumer use, and continued innovation. Even with limited visibility, AI-related revenues are already material and growing rapidly, with market penetration estimated to be below 1 percent. Underlying revenue growth, margin structures, operating cash flow, and capex intensity for most hyperscalers remain solid. That’s another clear distinction from the dot-com period.

Looking ahead, the roughly USD 3 trillion in cumulative AI infrastructure capex projected for the next three years is expected to be funded mainly through internal resources, meaning operating cash flow and private equity, with only about 40 percent coming from private credit or bond issuance. Although tech debt issuance has increased recently, especially among hyperscalers, net leverage across the sector remains generally well contained. Current credit default swap pricing shows only moderate stress in a few isolated cases and is nowhere near levels associated with prior bubble environments.

Despite recent volatility, the broader upward trend in equity markets appears to be intact. If history is any guide, corrections of 5 percent to 10 percent during major technology adoption cycles are a normal part of ongoing bull markets rather than a sign of fundamental deterioration.

Soy-ing goodbye to Chinese demand

Once just a staple of American agriculture, soybeans have found themselves at the heart of a high-stakes showdown. In the US-Chinese trade war, this unassuming legume became a symbol of economic leverage and farmers caught in the crossfire.

The US is a force to be reckoned with in the soybean market. In 2024, it produced approximately 118 million tons of soybeans, making it the world’s second-largest producer after Brazil, which harvested 169 million tons. Since US soybean production exceeds domestic demand, approximately half of the crop is exported.

That said, China is an even more dominant force. Fueled by its large livestock sector (China is the world’s largest pork producer) and its dominant aquaculture industry (the largest globally), the country imports over 100 million tons of soybeans annually. Historically, half of US soybean exports have ended up in China.

But times have changed. As trade tensions escalated, Beijing imposed tariffs and other duties on US agricultural products. This made US soybeans less competitive for Chinese buyers compared to, for example, Brazilian ones.

In May, China ordered its importers to halt US soybean purchases. By September, China had imported zero US soybeans. This was a big blow to US farmers— a key Republican voter base already struggling with high production costs.

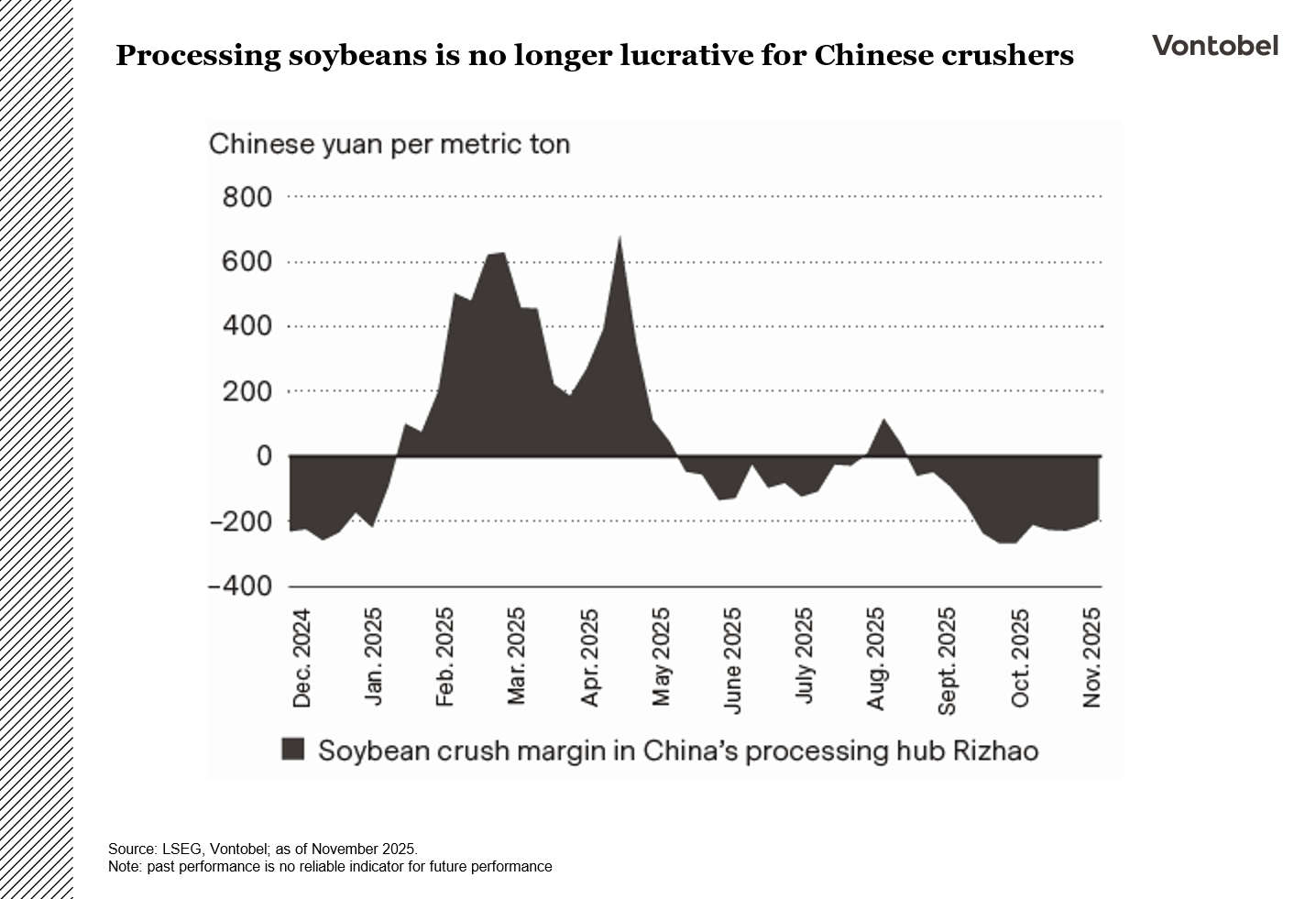

Soybeans even found their way onto the agenda of the meeting between US President Donald Trump and Chinese President Xi Jinping in South Korea. In the run-up to the summit, soybeans rallied 8.8 percent. However, that optimism faded when the White House announced that China would only buy 12 million tons by the end of the year (2024: 21 million tons). While China has since ordered a few cargoes, it’s not certain that it will significantly augment its purchases. After sharply increasing imports from South America, Chinese soybean stocks reached a record 10.3 million tons in early November. This has led to a glut in soymeal, which is used to fatten animals. As a result, Chinese processors, known as crushers, have been grappling with negative margins since August.

Looking ahead, the soybean market is likely to reflect this “new normal”: China will likely continue to buy what it needs at the lowest possible price, while US farmers can’t count on China returning to previous import volumes without a significant policy shift. And South American exporters are happy to fill the gap.

A strong franc is keeping Swiss inflation too low for comfort

Inflation is uncomfortably low, but not weak enough to force the Swiss National Bank (SNB) into dramatic action. As long as prices hover around zero and the franc is strong but not soaring, the most likely path is a long hold at 0 percent, with the SNB stressing patience and data dependence. A return to negative rates would likely need a clear, persistent slide into deflation, while a late, modest hike would require a much stronger global backdrop and domestic inflation above forecast.

Swiss inflation has slipped back to zero, piling pressure on the SNB to lean against a strong franc and revive price growth. Headline CPI20 was unchanged at 0.0 percent in November from a year earlier, versus expectations of 0.1 percent. Core inflation eased further to 0.4 percent from 0.5 percent. The franc’s safe-haven role has pushed it near decade highs against the euro and the US dollar, reducing import prices and dragging inflation down.

The numbers are a setback for the SNB, which has been counting on inflation to rise toward year-end and into 2026. In September, policymakers argued that cutting back to zero would support a gradual pickup in inflation. Their options are limited, and each one carries risks. Renewed foreign-exchange intervention would swell an already large balance sheet and risk irritating US authorities. A return to negative rates could strain parts of the financial system, revive concerns about bank profitability, and weaken public support. SNB President Martin Schlegel has repeatedly said that the bar for reintroducing negative rates is higher than for a normal cut.

The SNB will likely want clearer evidence of falling prices before acting, so interest rates are likely to stay at 0 percent through next year while officials monitor the franc and incoming data. Risks run both ways. On the downside, a hit to exports, renewed franc strength, and several months of negative headline inflation that push the SNB’s conditional inflation forecast clearly below zero could trigger a temporary return to negative rates in response to rising deflation risk. On the upside, a faster global recovery, a softer franc, and domestic inflation drifting above the conditional inflation forecast could justify a 25-bps hike later on, mainly to keep real rates from sliding too far below zero and to rebuild policy space. Even then, any tightening path would likely be shallow and reversible. For now, that still looks like a low-probability tail.