Investors’ Outlook – Handle with care

Markets entered June relatively well-pressed. While a few trade creases remained (such as the US doubling tariffs on steel and aluminum imports), US President Donald Trump’s tariff delays gave countries time to ponder their next steps, and new US-China talks helped smooth sentiment.

Creasing conflicts

But Israel’s attacks on Iranian nuclear facilities abruptly shattered the calm and drove crude oil prices sharply higher. As of today, it seems that the Multi Asset Boutique’s baseline scenario (attacks by Israel, retaliatory strikes by Iran, followed by limited US military involvement, and a temporary rise in crude oil prices to USD 70 to 80 per barrel) has materialized.

Vontobel’s Multi Asset Boutique expects there is currently little reason to fear significantly higher inflation. Monetary policy has eased but is not excessively accommodative. And a significant surge in demand is unlikely as global economic growth continues to slow.

Still, Middle East tensions have added another layer of uncertainty to the US Federal Reserve’s already complicated task. It held interest rates steady in June and made upward revisions to both inflation and unemployment expectations. The European Central Bank (ECB) delivered another interest rate cut, with markets expecting at least one more cut by year-end. The Swiss National Bank brought its key interest-rate to zero to manage the franc’s strength and deflationary pressures.

Ironing out Europe’s future?

European stocks have had an impressive run this year. Major European equity indices have climbed between 20 percent and 25 percent, with Germany’s DAX Index even rising more than 30 percent. At the start of the year, the rally was mostly driven by valuations as many European stocks were trading at a significant discount to their US counterparts. In the months that followed, however, optimism took over: hopes for an end to the war in Ukraine, hopes for generous stimulus packages… and maybe even hopes for a kind of “Make Europe Great Again.”

European stocks are no longer as cheap as they were at the beginning of the year but they’re still more affordable than US stocks. That valuation gap reflects, among other things, investors’ belief that the Eurozone is less productive than the US or other regions. There are several reasons for this productivity lag, one of the biggest being the fragmentation of the Eurozone itself.

Despite sharing a common currency, the 20 countries that make up the Eurozone each maintain different tax systems, labor markets, and economic policies. This fragmen- tation makes it harder for companies to operate efficiently across borders and limits economies of scale. Their capital markets are similarly fractured along national borders. The European Union itself acknowledges that integration of European capital markets remains “relatively modest.”2 Well-functioning, integrated capital markets are important for helping domestic markets grow and for supporting innovative start-ups and scaleups. A fully unified capital market could also boost cross-border investments, attract more foreign capital to the region, and strengthen the euro’s role as a global investment currency.

So it doesn’t come as a surprise that the US is the leader in the development and adoption of new technologies, especially in fields like artificial intelligence, big data, and cloud computing. US tech giants like Google, Amazon, Apple, and Microsoft drive productivity through innovation. Europe has its own share of innovative firms, but they often struggle to scale up as quickly or assertively.

External pressures

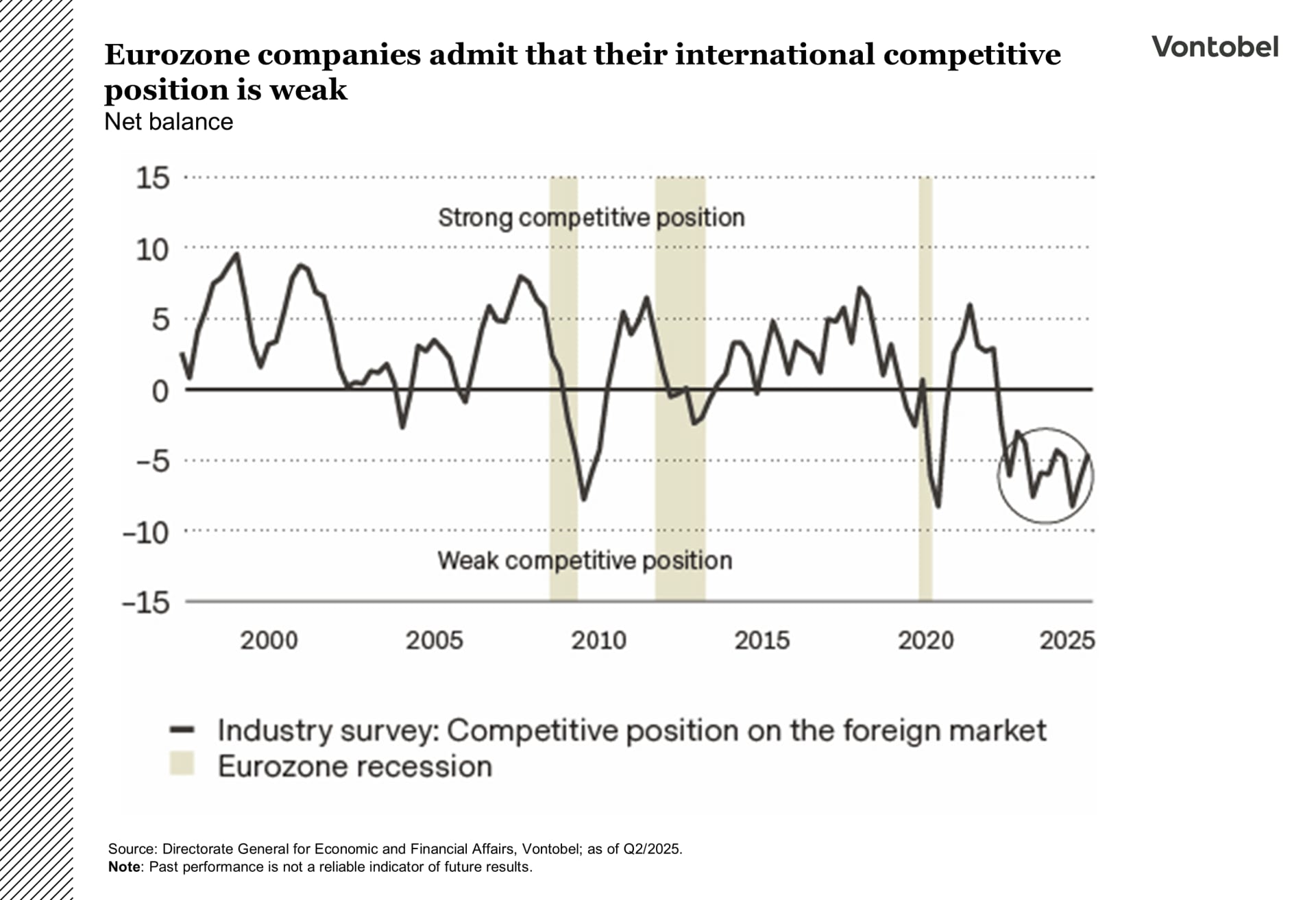

US President Donald Trump’s “America First” agenda has strained transatlantic ties and challenged Europe’s export-driven economic model. In Germany, the Euro- zone’s largest economy, exports of goods and services account for more than 40 percent of gross domestic product (GDP). Countries like Spain (36.7 percent), France (33.5 percent), and Italy (32.3 percent) are similarly ex- posed to global trade flows. In addition, the war in Ukraine continues to weigh on business and consumer confidence, with growing concerns that Russia could eventually threaten more European nations. Rising security threats have also sparked calls for increased defense spending.

Trump has repeatedly criticized NATO allies for falling short on defense budgets and has even threatened to withhold US support if they don’t contribute more—he’s floated a target of 5 percent of GDP. While European defense spending rose 11.7 percent to EUR 423.3 billion last year, hitting that 5 percent mark remains far off for most countries given current budget constraints.

Europe also faces pressure from the East. China is flood- ing global markets with cheap high-tech products, such as electric vehicles and solar panels, posing a threat to key European industries. At the same time, European companies continue to struggle to gain a meaningful foothold in the Chinese market.

Add to that the lingering aftershocks of past crises. The Eurozone still bears scars from the euro crisis that followed the 2008 financial meltdown3. As shown in chart 1, investment spending in Europe collapsed during that time and has yet to fully recover.

And on the domestic front, immigration remains a hot-button issue. Expectations around integration, hous- ing, and internal security often fuel populist and anti-EU political movements, particularly in countries like Germany and France.

Given all these headwinds, it may not be surprising that European businesses take a fairly pessimistic view of their global competitiveness (see chart 2).

Progress has been made

Despite the gloom, the Eurozone has made real struc- tural progress in recent years. One standout achievement is the sharp reduction in structural unemployment. Since the depths of the euro crisis, the Eurozone’s unemployment rate has been cut in half (April 2025: 6.2 percent). The improvement has been even more dramatic in southern Europe, where unemployment peaked above 18 percent but is now down to just 7.7 percent. Households have also gotten their finances in better shape, with debt levels now significantly lower than they were after the financial crisis or the pandemic (see chart 3).

The banking sector has made strides as well. The share of non-performing loans (NPLs), especially in countries like Greece, Italy, Spain, Portugal, and Ireland, has dropped from more than 10 percent during the crisis to under 3 percent today amid economic recovery and key reforms. Banks are also better capitalized, with stronger Tier 1 capital ratios.

Years of ultra-low interest rates have also helped reduce the Eurozone’s net interest burden. As a percentage of GDP, interest costs have fallen from more than 5 percent at the height of the euro crisis to just 3 percent—that’s a far more comfortable position than in the US, where they now exceed 8 percent. That said, some countries, like Italy (over 6 percent) and Spain (4 percent), still face high debt-servicing costs.

Short-term tailwinds

On top of those longer-term improvements, there are also short-term positives. Ironically, Donald Trump might be one of them. His first term sparked a handful of minor but positive reforms in Europe. The pressure is on again with his second term—one could argue that European leaders have no choice but to act.

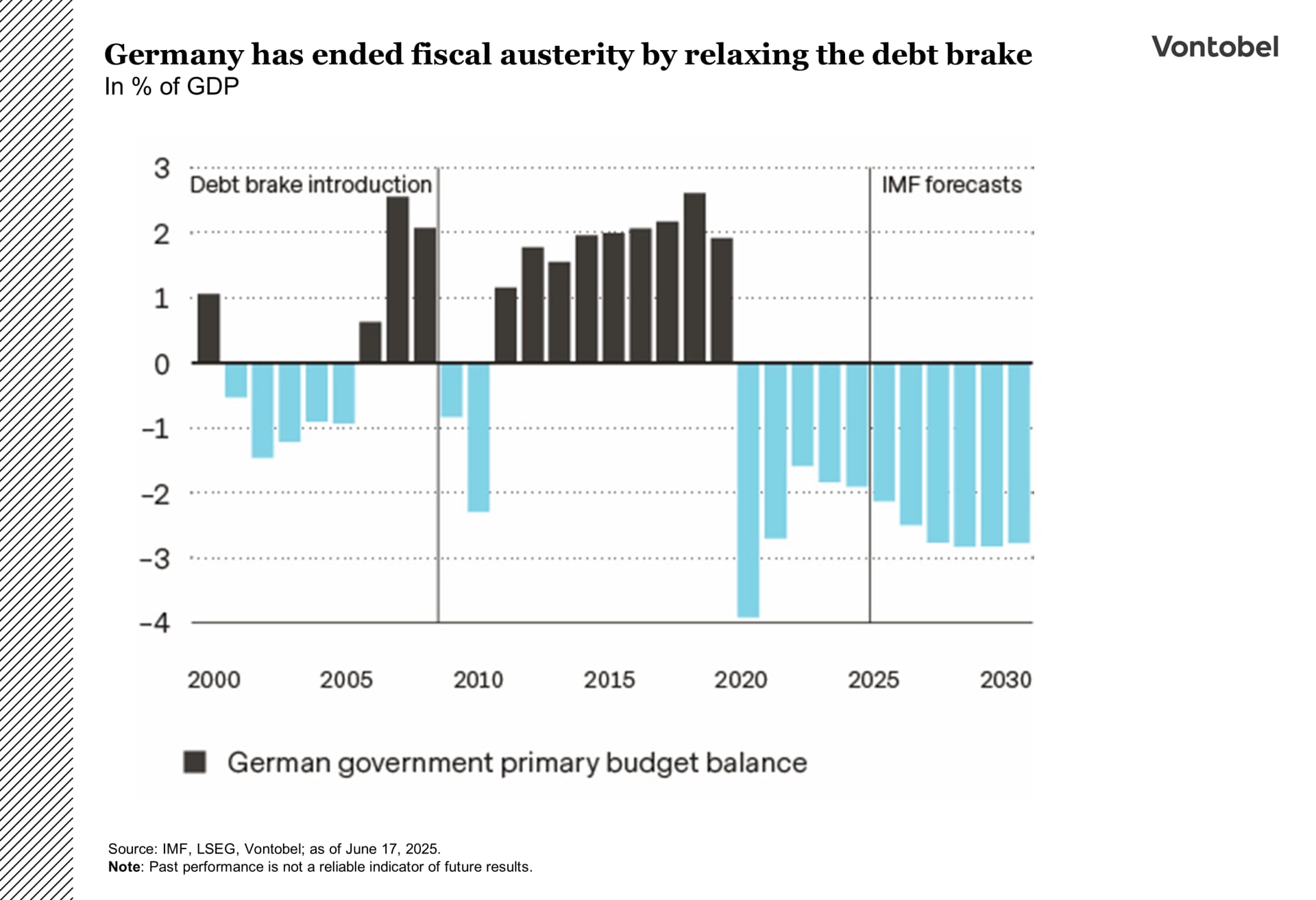

A prime example is Germany’s debt brake reform (see chart 4). In February, then-chancellor candidate Friedrich Merz flatly rejected any changes to Germany’s balanced-budget rule. But by March, citing the “threats to freedom on our continent”, he called for a constitutional amendment to allow hundreds of billions of euros in debt-financed investment for defense and infrastructure. This shift appears to have had a ripple effect across Europe: other countries have also announced higher defense spending, though not at the same scale. According to NATO Secretary General Mark Rutte, all NATO members are on track to hit the alliance’s 2 percent spending target this year.

Industrial policy is gaining momentum as well. Former ECB chief Mario Draghi presented a comprehensive competitiveness report in September 2024, highlighting the weaknesses of the European economy, which European Commission President Ursula von der Leyen used as the foundation for a new “Competitiveness Compass.” According to comments by von der Leyen in late January, Europe has “everything it needs to succeed in the race to the top,” and that regaining competitiveness is now needed to overcome weaknesses. The Competitiveness Compass is meant to translate Draghi’s recommendations into an actionable roadmap. “So now we have a plan,” she said. “We have the political will. What matters is speed and unity. The world is not waiting for us. All member states agree on this. So, let’s turn this consensus into action.”

The plan focuses on three core areas: 1) Closing Europe’s innovation gap, 2) aligning decarbonization with competitiveness, and 3) reducing dependencies and strengthening security. A range of initiatives stem from these priorities, including a “Competitiveness Fund,” a “European Savings and Investment Union,” and an “Omnibus Initiative” aimed at cutting red tape.

Another encouraging development: inflation is returning to normal. In May, consumer price inflation in the Eurozone fell to 1.9 percent, below the ECB’s 2 percent target.

Wage growth is also slowing. The ECB’s wage tracker, based on ongoing collective bargaining agreements, projects a 3.1 percent average increase in 2025, down from 4.7 percent in 2024. Excluding one-time bonuses, wage growth may fall to 2.9 percent, down from 4.9 percent.

This gives the ECB room to continue easing monetary policy. In June, it cut interest rates for the eighth time, bringing the deposit rate to 2 percent. Although the cen- tral bank signaled it may pause over the summer to reassess the outlook, markets are still pricing in at least one more rate cut by year-end. Ongoing rate normalization could give the struggling Eurozone economy a needed boost.

What would it take to make Europe “great” again?

The Multi Asset Boutique’s in-house “Make Europe Great Again” checklist, only two out of 10 boxes are currently checked (see chart 5). Not all criteria have to be met, but it likely requires more than two. With some initial steps taken and the sails now set, all Europe needs is a bit more tailwind to breathe new life into the old continent.

Set to delicate

The Fed held rates steady at 4.25 – 4.5 percent and reaffirmed guidance for two interest-rate cuts this year, but new projections point to slower growth, stickier inflation, and growing internal disagreement. The path to easing now looks more uncertain, with September now likely the earliest plausible window—data permitting.

The Fed’s updated forecasts show 2025 GDP revised down to 1.4 percent (from 1.7 percent), core PCE inflation10 up to 3.1 percent, and unemployment expected to rise to 4.5 percent. These stagflation-like conditions complicate the Fed’s balancing act between supporting growth and keeping inflation under control.

Divisions within the Federal Market Open Committee (FOMC) are growing. Two distinct camps are emerging: one favoring cuts, citing slowing growth and rising unemployment, and the other calling for patience, pointing to persistent inflation. As of June, seven of the 19 members now expect no cuts this year, up from four in March, despite the median still signaling two. Projections for rate cuts in 2026 and 2027 were also trimmed, suggesting a slower pace of normalization. Still, the FOMC voted unanimously to hold rates steady for now. At his press conference, Chair Jerome Powell emphasized caution: “We’re well positioned to wait and learn more.” That phrasing reinforces the Fed’s data-dependent approach, while leaving the door open to action if needed.

Inflation risks remain, particularly from tariffs and geopolitical tensions, especially in the Middle East, which could push energy prices higher. Powell acknowledged the delayed impact of tariffs: “Someone has to pay for them.” A September cut remains possible, but only if disinflation can be confirmed and the labor market softens further. Until then, the Fed is poised to sit tight, watching both sides of its mandate.

Market expectations for the Fed’s terminal rate have remained stable (see chart 1), reflecting confidence that recent inflation data, labor market conditions, and policy signals are consistent with a higher-for-longer stance.

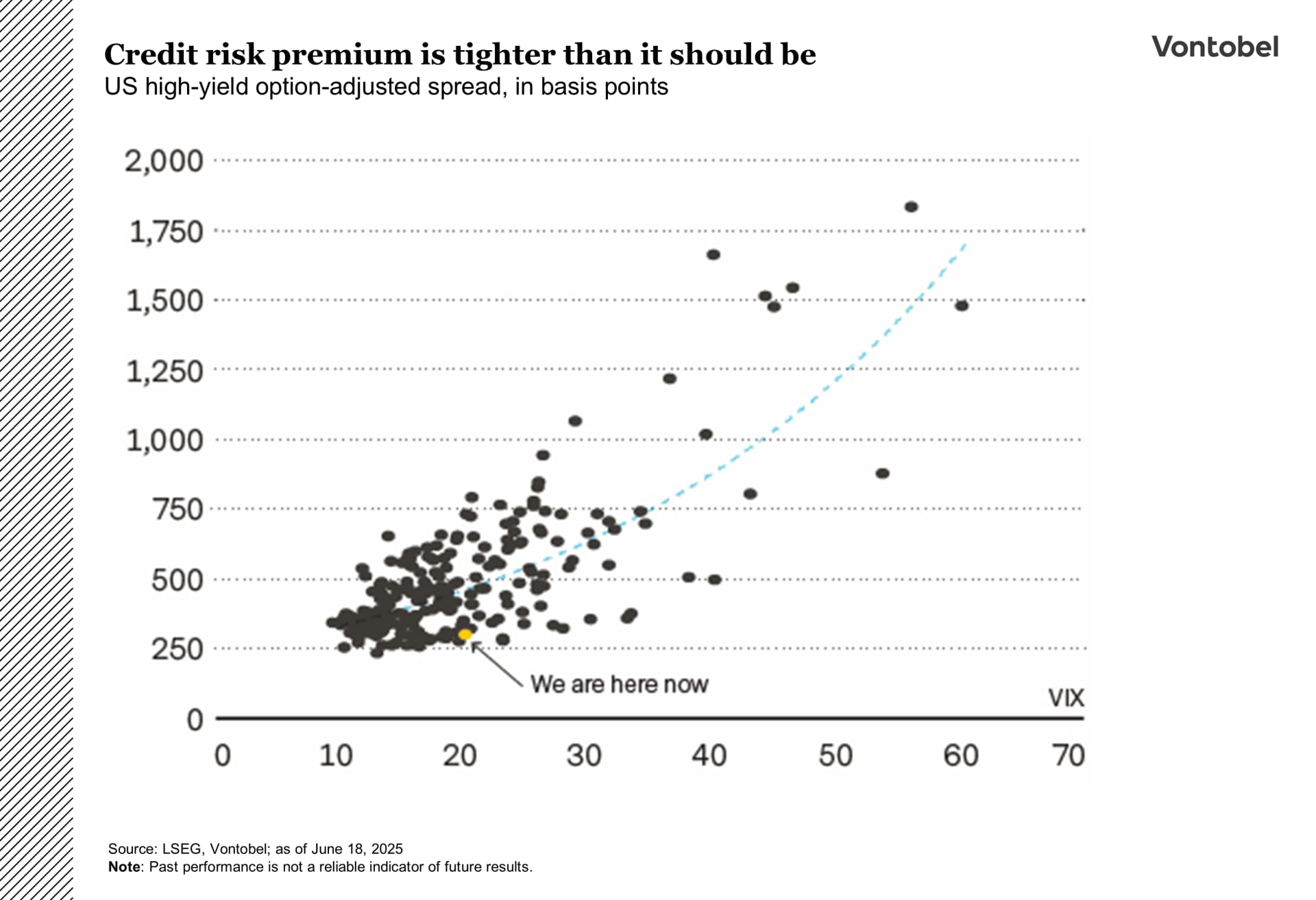

Spreads defy volatility

Credit markets are showing signs of complacency. Given current volatility levels, spreads would typically be wider (see chart 2). The sharp rally and spread compression after spring’s stress episode may have overcorrected, leaving spreads misaligned with underlying macro and credit risks. Tighter spreads now leave little cushion should volatility pick up or fundamentals deteriorate. The investment- grade risk premium looks rich relative to the level of market stress implied by the Volatility Index (VIX), raising questions about downside protection and growing vulnerability in credit valuations.

Sorting through Europe’s mixed signals

As we move into the second half of the year, it’s clear that markets have just been through a turbulent spin cycle, capped by the outbreak of conflict in the Middle East. So, what may lie ahead?

Markets remain laser-focused on what really moves the needle: inflation, central banks, the trajectory of monetary policy, and their impact on economic growth.

In Europe, after a strong first quarter, equities began to lose momentum by the end of the second one. Much of the outperformance in the first half of the year came from the cyclical sectors, particularly financials (mainly banks) and industrials (mostly defense-related stocks). Using the German DAX Index as an example, defense-related names alone accounted for roughly 30 percent of the index’s year-to-date gains. Stripping away these cyclical drivers, the broader European market is relatively flat in local currencies, similar to Switzerland’s staples- and healthcare-heavy market or the US, where performance was dragged further by dollar weakness. What stands out is policy contrast between the US and Europe. While US monetary policy remains tight, Europe has been moving toward fiscal easing. With the ECB keeping interest rates low, the Multi Asset Boutique expects European earnings growth is poised to rebound after years of stagnation (see chart 1). A key catalyst here is Germany’s historic fiscal stimulus, announced earlier this year, focused on defense and infrastructure.

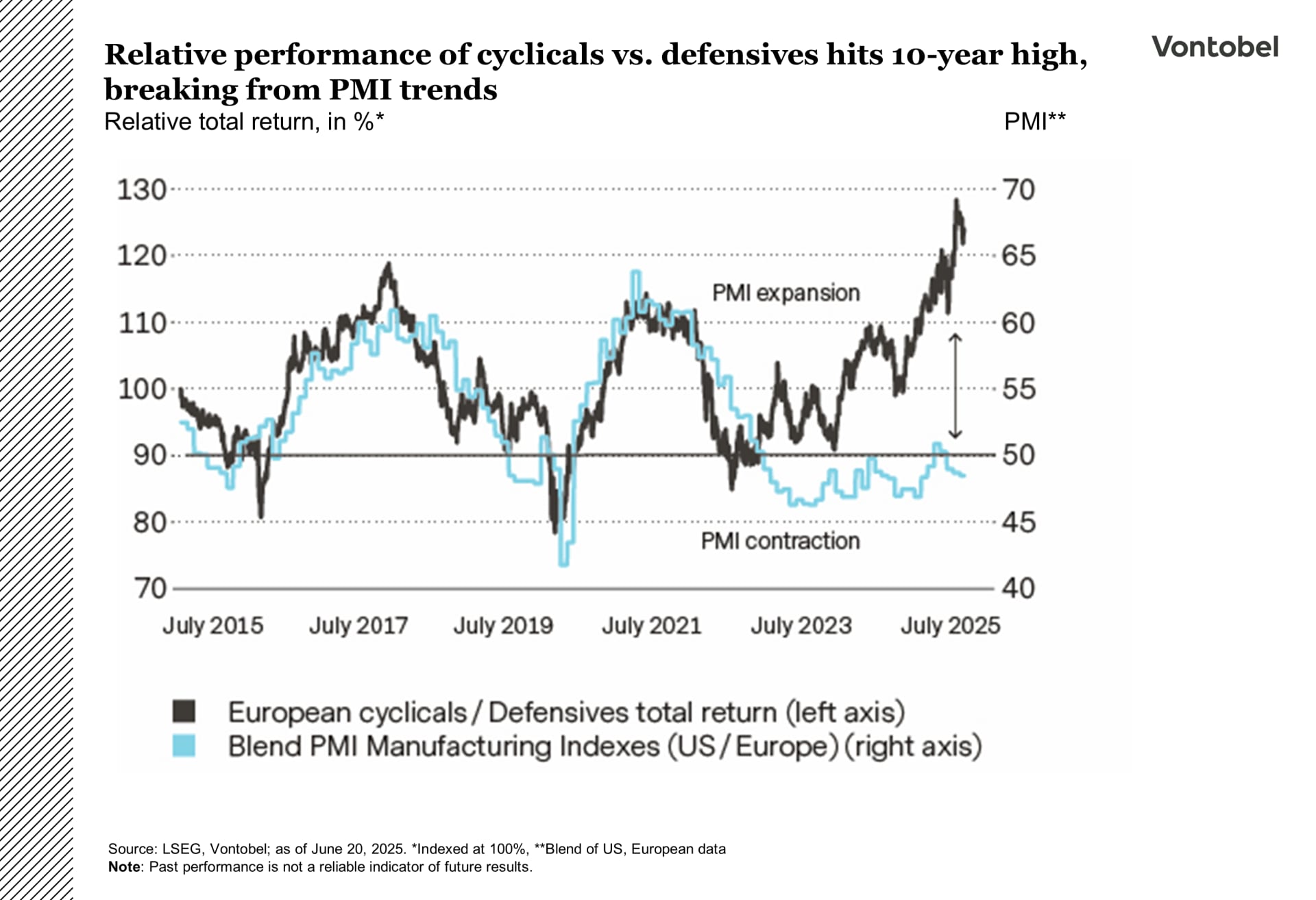

Still, one key question is whether the good news is already priced in. Valuations in some sectors look stretched, and global institutional investors’ surveys show long positioning in European stocks, especially banks, remains a crowded trade. It’s also worth highlighting that the relative performance of cyclical stocks versus defensives11 has reached a 10-year high—an extreme that is typically supported by strong PMI12 data, which is notably lacking in the current environment (see chart 2). This means Purchasing Managers’ Indices (PMIs) will need to improve to sustain the trend markets have already priced in. On top of that, as central banks cut rates, banks—so far among the rally’s main engines—may begin to lose steam.

Add to this mix the looming July deadline for Donald Trump’s 90-day tariff threat, and there may be a recipe for renewed volatility through summer.

A loud roar from the oil market

There’s a saying among commodity analysts: “Oil markets always pay attention when Iran is involved.” After a lackluster performance for most of the year, “Operation Rising Lion” temporarily drove crude oil prices above USD 80 per barrel.

As of today, the Multi Asset Boutique’s base-case scenario has been confirmed. In this scenario, the team anticipated Israeli attacks and Iranian retaliatory strikes, followed by limited US military involvement. Consequently, the team projected no or only minimal impacts on oil supply and only temporarily higher oil prices (USD 70 to 80 per barrel). Thereafter, it was assumed the situation would stabilize.

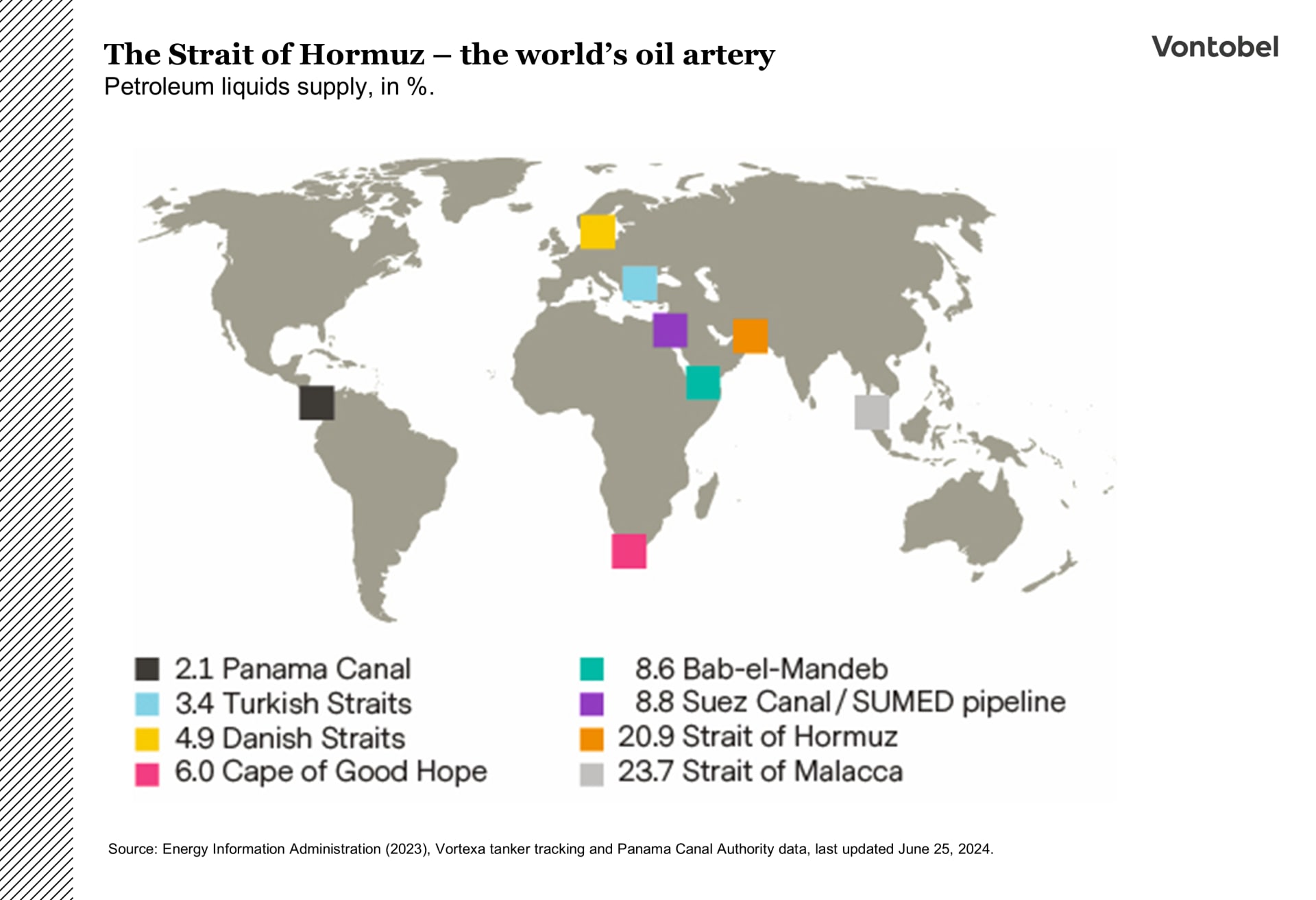

As in previous conflicts, Iran has once again threatened to close the Strait of Hormuz which is effectively con- trolled by Iran. Often referred to as the world’s oil artery, approximately 20 percent of global petroleum product shipments pass through this chokepoint (see chart 1). Nearly two-thirds of the volume consists of crude oil from Iran, Kuwait, Saudi Arabia, Qatar, and the United Arab Emirates, while the remainder is made up of oil products and natural gas. The closure of the Strait remains the largest tail risk, which could drive prices well above USD 100.

However, this scenario is considered unlikely. There’s a reason why Iran has never followed through on its threat to close off the Strait – by doing so, it would effec- tively cut off its own oil exports and, consequently, its revenue streams. The Multi Asset Boutique expects Iran would resort to such a drastic step only if it feared a forced regime change.

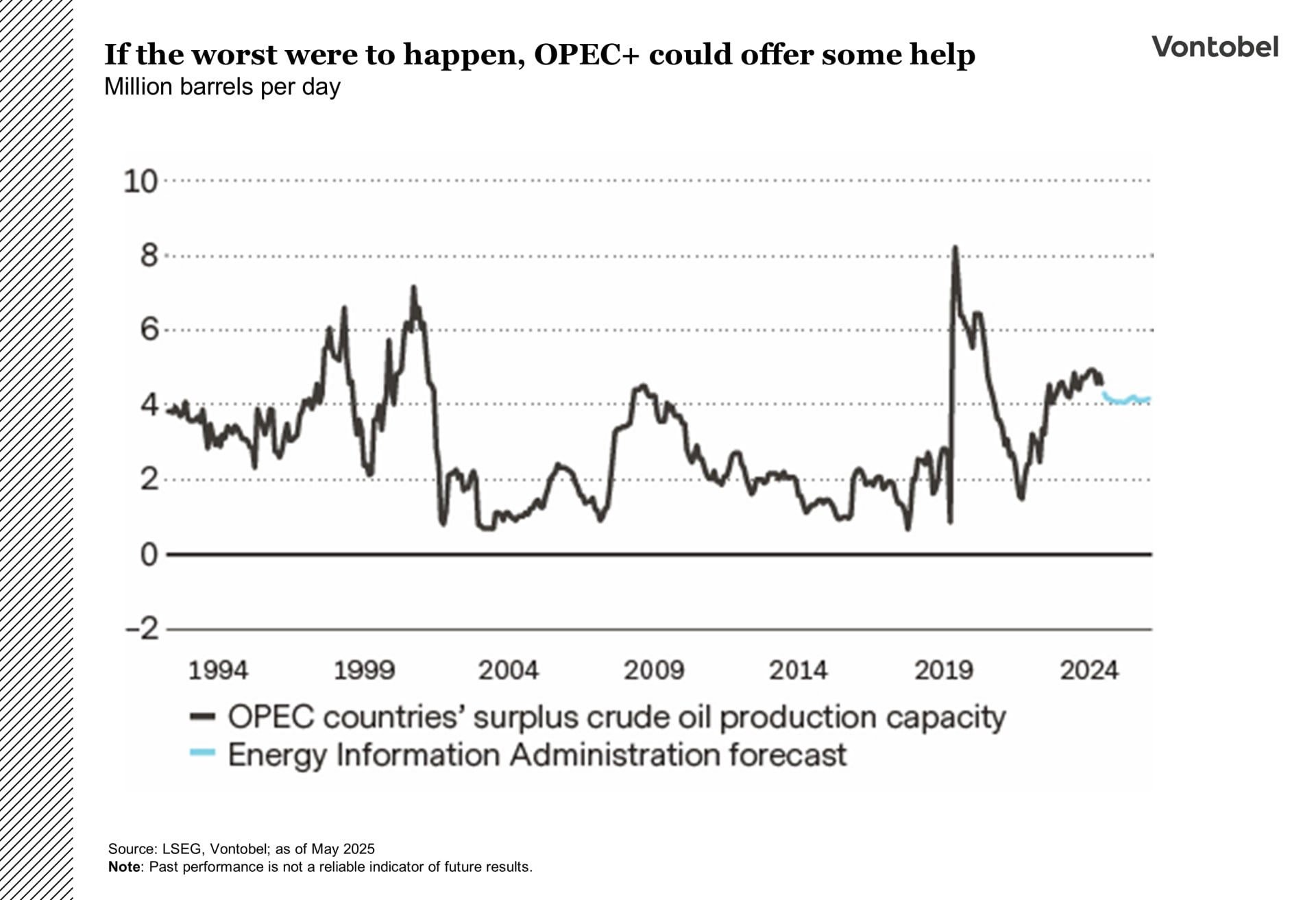

If, contrary to expectations, the Strait were to become embroiled in the conflict, the US Strategic Petroleum Reserve (SPR15) and / or OPEC+ could step in to help (see chart 2). However, there are some caveats. Following multiple emergency withdrawals, the SPR is depleted and now holds “only” 402 million barrels. As for OPEC+, doubts remain about the actual extent of spare capacity. Years of production cuts and reduced investments following Covid-19 have left some oil fields and facilities unable to resume operations easily. Likely, only Saudi Arabia and the United Arab Emirates would be able to ramp up production quickly.

Beyond the geopolitical headlines, the Multi Asset Boutique’s crude oil forecast remains subdued through the end of 2025. This is due in part to uncertainties surrounding trade wars, associated growth concerns, and additional supply from other producers (Brazil, Guyana, and Canada).

Permanent stains on the greenback?

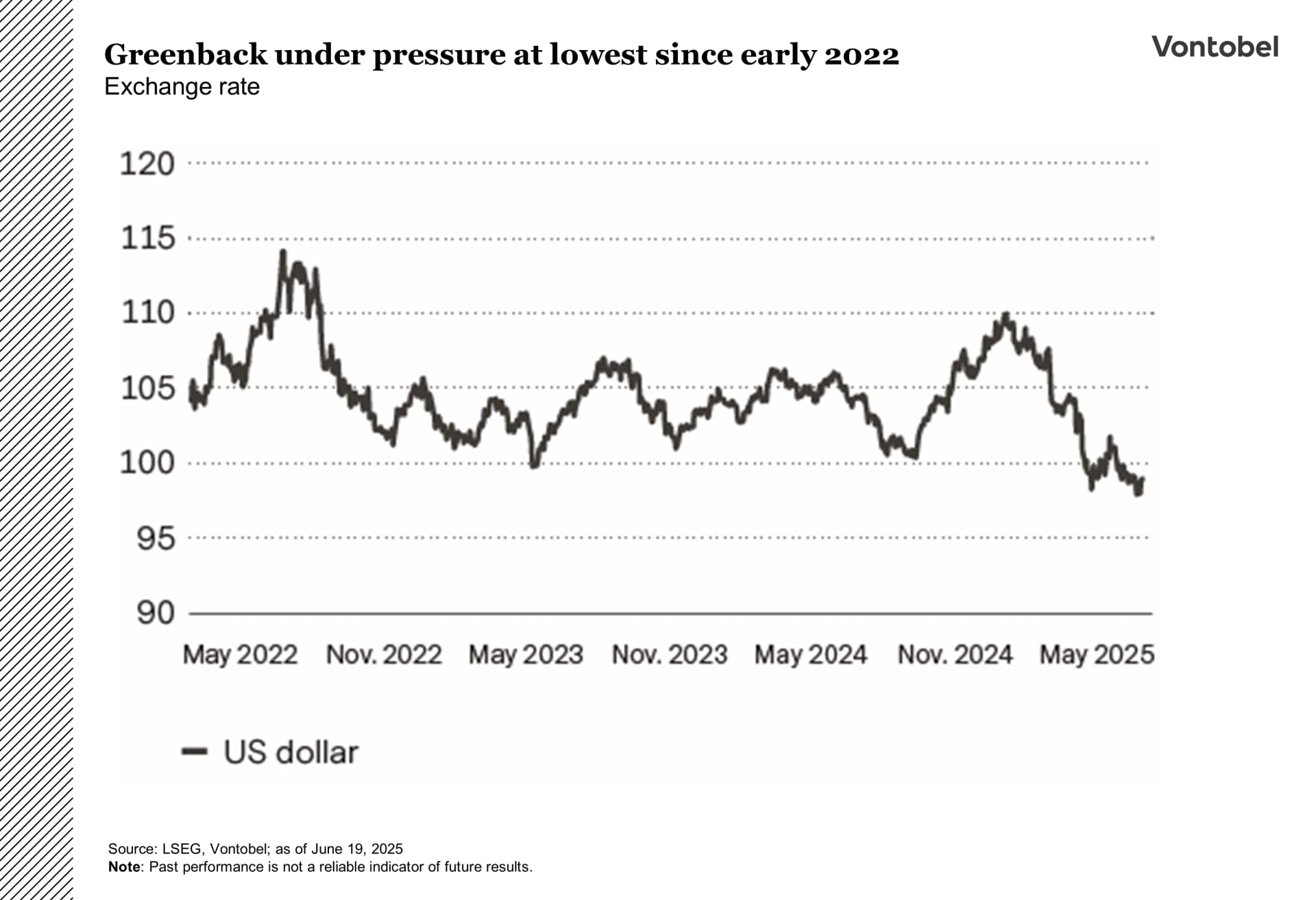

The US dollar still anchors the global monetary system. It commands the largest share of official reserves, denominates most cross-border debt and trade credit, and accounts for roughly 40 percent of daily FX turn- over. Yet its pre-eminence is no longer taken for granted. Two forces—shifting trade patterns and widening fiscal stress—are prompting a reassessment by reserve man- agers and currency investors (see chart 1).

US tariff measures, coupled with a gradual re-routing of global supply chains, are likely to reduce the share of world commerce settled in dollars. Every time an exporter chooses another invoicing unit, baseline demand for dol- lar liquidity inches lower. Central banks seem to be drawing similar conclusions: IMF data show the dollar’s slice of reported reserves falling for nine consecutive quarters, while official gold holdings rise. The pace is measured, but the intent appears strategic.

Domestic fundamentals reinforce the drift. Net interest outlays now rival defense spending, and annual borrowing needs exceed USD 2 trillion through 2029. With Con- gress preparing yet another round of spending bills—and another debt-ceiling vote—long-bond term premia have widened as investors demand compensation for fiscal risk once viewed as immaterial.

This growing policy-driven risk premium is already visible in FX-option pricing and reinforces the market’s increas- ingly entrenched bearish view on the dollar. Option skews suggest that weakness into 2026 will stem not only from cyclical forces such as Fed cuts and narrower interest dif- ferentials, but also from a structural rethink of how the US engages with global capital. The implication is a weaker and more volatile dollar as the traditional rules that underpin reserve-currency status begin to fray. USD / CHF options make the point explicit (see chart 2): as of 19 June, market-implied probabilities of the pair trading below 0.80 stand at 51.8 percent within nine months, 57.1 percent in one year, and 69.3 percent over two years, while the probability assigned to the 0.80 – 0.85 range shrinks steadily. Such pricing signals structural repricing rather than short-term caution.

In sum, the greenback now faces a dual challenge: a cooling domestic economy and an expanding fiscal premium layered over a policy backdrop that no longer guarantees unfettered capital access. Reserve status will not vanish overnight, but marginal shifts in trade invoicing, portfolio allocation, and perceived policy credibility are set to exert more influence on exchange-rate dynamics than in previous cycles. The balance of risks points toward a measured, if occasionally volatile, depreciation path