Investors’ Outlook: Kicking off the year

January began with a tale of two forces—optimism fueled by strong US economic data and unease over inflation, policy shifts, and global market ripples.

The US labor market provided a bright spot. Nonfarm payrolls surged by 256,000 in December, well above the 155,000 forecast, and the unemployment rate ticked down to 4.1 percent. After two years of cooling, the labor market seemed to find its footing.

Markets, meanwhile, braced for the impact of Trump’s campaign promises of increased spending and economic growth. Paired with fears of rising deficits and inflation, investors reassessed how aggressively the Fed might cut rates in 2025. Bond markets bore the brunt of these shifting expectations: US 10-year Treasury yields soared past 4.7 percent, pushing global yields higher. Bucking the trend, China’s 10-year yields hit record lows, reflecting the country’s struggles with weak growth and deflation fears.

The Multi Asset Boutique believes that the economy will continue to grow in 2025, that inflation will stay under control, and that (most) major central banks will proceed with gradual rate cuts. While the Fed held rates steady in January and emphasized it was in no hurry, the Multi Asset team anticipates the Fed to cut interest rates back to what is considered “neutral” territory this year as soon as further downside surprises on the inflation front become more apparent. This would also bring down yields of 10-year Treasury bonds towards 4 percent, and support stock markets.

Across the Atlantic, the picture is less rosy. The Eurozone faces an uphill battle as economic activity remains subdued, and consumer and business confidence remains weak.

“Ja, ja, ja, jetzt wird wieder in die Hände gespuckt, wir steigern das Bruttosozialprodukt…”

Germany’s economy eked out a mere 0.1 percent growth in the third quarter of 2024. Once the powerhouse of the Eurozone economy, exports fell by 2.8 percent month-on-month in October. Meanwhile, industrial production remains more than 10 percent below pre-Covid-19 levels—almost five years after the pandemic began. According to economic forecasters, things are unlikely to change anytime soon. The Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) expects Germany to “bring up the rear among OECD countries”, expanding at a meager 0.7 percent pace in 2025. The Federation of German Industries (BDI) paints an even bleaker picture, forecasting a 3 percent drop in production for 2024, with “no improvement in sight” for 2025. Or, in the words of BDI President Siegfried Russwurm, “Germany’s business model is in serious jeopardy, not someday, but here and now. About one-fifth of industrial value creation is at risk".

How did this spectacular fall from grace happen? Much has been said about the Covid-19 pandemic, the Russia-Ukraine war, and the energy crisis as contributors to Germany’s economic struggles. But a closer look at chart 1 reveals that cracks in Germany’s industrial foundation appeared long before these recent crises. For instance, Germany’s industrial production peaked years before Covid-19 or the war in Ukraine emerged. This suggests deeper structural challenges may be at play.

One such challenge is Germany’s heavy reliance on exports. Exports of goods and services account for over 40 percent of the country’s gross domestic product (GDP)—a stark contrast to the US (11 percent) or the Eurozone (19 percent, all data as of 2024). While Germany’s export-driven growth model has been a cornerstone of its economic success for decades, it also leaves the economy vulnerable to external shocks and fluctuations in global trade. This vulnerability is particularly pronounced in Germany’s relationship with China, the world’s second largest economy. For decades, China was a major importer of German goods, driving German exports to China from less than 2 percent in 2000 to nearly 10 percent in 2020 as a percentage of total exports. However,

by 2024, that figure had fallen to just 5 percent as China shifted from a loyal customer to a formidable competitor, especially in key industries (see chart 2).

Then there’s the problem of an energy strategy gone wrong. Like many European countries, Germany is a net energy importer, meaning it cannot meet all its energy needs domestically and is therefore dependent on foreign suppliers. In early 2022, Germany sourced 55 percent of its natural gas from Russia. However, Russia’s invasion of Ukraine unleashed a chain reaction: supply disruptions, a massive spike in energy prices, and a frantic scramble for alternative suppliers.

The energy crisis of 2022 reignited debates about energy security and accelerated the push toward renewable energy. To Germany’s credit, significant progress has been made. According to estimates by the Fraunhofer Institute for Solar Energy Systems, Germany’s proportion of renewable energy in the electricity mix, i.e., the power that comes from the socket, was roughly 57 percent in 2023. However, this does not automatically translate to low and stable prices. When there is no wind and sunlight, electricity generation from wind and solar power plants comes down. As a result, prices on the electricity exchanges rise. This was the case in December 2024, when day-ahead electricity prices spiked to over EUR 900 per megawatt hour before dropping back to EUR 100 shortly thereafter.

In theory, nuclear power could provide a buffer against such fluctuations. However, Germany shut down its last three remaining nuclear power plants in early 2023, a decision that has sparked challenges both domestically and internationally. Sweden has been particularly vocal in its criticism of Berlin’s nuclear phase-out, accusing it of “hypocrisy”. In December 2024, Swedish Energy Minister Ebba Busch criticized Germany of blocking EU financing for new fossil-free baseload power projects. She argued, “It’s one thing for the Germans not to want nuclear power for themselves, but it’s another to prevent other countries from accessing these funds.” Ultimately, while Russia’s supply disruptions may have been a tipping point, Germany’s energy crisis began before Russia invaded Ukraine (see chart 3).

Waning competitiveness

Another significant challenge is Germany’s competitiveness. Competitiveness (or the lack thereof) spans several dimensions. Take the country’s relatively stringent labor market regulations as an example. Unlike the US, German law requires valid reasons for termination, formal warnings, and strict adherence to notice periods. These rules, combined with a highly unionized workforce, make it relatively difficult for companies to dismiss employees.

Competitiveness is also linked to demographics. Germany’s fertility rate (the number of births per woman) was just 1.5 in 2022, at the low end of its peer group, according to World Bank data (US: 1.7, France: 1.8). Additionally, the CIA World Factbook (2023) ranks Germany among the top 10 countries globally with the highest median age, at 46.7 years. An aging population has profound economic implications. As the workforce shrinks, labor shortages in certain sectors become more likely. Official estimates suggest Germany could face a shortfall of seven million skilled workers by 2035. This tightening labor market could push wages higher, exacerbating cost pressures for businesses. At the same time, an aging society demands higher public spending on pensions and healthcare. These rising costs could strain public finances, potentially leading to higher taxes. Increased immigration could help offset some of these demographic challenges (but remains a politically sensitive issue).

Then there’s also Germany’s high corporate tax burden. According to the OECD tax database, Germany’s statutory corporate income tax rate stood at about 30 percent in 2024. This put it at the top of its peer group (vs. France, the Netherlands, and the US: around 25 percent; Sweden, Finland, and Switzerland: around 20 percent). Another structural challenge is Germany’s investment backlog. The country’s net fixed capital formation, expressed as a percentage of GDP, lags behind peers such as the US and the Eurozone. Germany’s reluctance to spend also becomes evident when looking at its aging equipment capital stock (average age in Germany: 7.3 years, Eurozone: 6.7 years, US: 6.1 years). At some point, aging capital stock requires reinvestment or quality will suffer.

Room for optimism

Despite these challenges, the picture is not entirely bleak. Due to years of fiscal discipline, Germany’s general government gross debt, expressed in percent of GDP, is significantly below that of its peers. This provides the country with financial “wiggle room” (see chart 4). It may well be that one day Germany will overcome its debt aversion and start to invest more. Even former Chancellor Angela Merkel—once dubbed Europe’s fiscal scourge—recently voiced support for relaxing the country’s “debt brake” to spur investments.

One should also not forget that the German economy can produce more than just cars (see chart 5). True, the automotive industry accounts for a sizable chunk of Germany’s exports. In 2023, machinery and other transport equipment accounted for 26 percent of the country’s exports, and road vehicles for 12 percent. However, the country also plays a significant role in the chemical (14 percent) and services industry (18 percent).

Potential relief could also come from lower gas prices. A wave of new liquefied natural gas (LNG) projects is expected to come online in the coming years. According to the International Energy Agency’s World Energy Outlook 2024, global supply is projected to outpace demand, potentially creating a surplus that could last well into the 2030s. This could provide support to many energy-intensive German industries (World Energy Outlook, Okt. 2024).

Then there’s Germany’s innovative power. At over 3 percent of GDP, Germany’s research and development (R&D) expenditure is within striking distance of the US (3.5 percent). It also significantly outpaces the Eurozone average of 2.3 percent (World Bank, 2021). This could translate into new, innovative products “Made in Germany” (note: the German automotive industry in particular invests heavily in R&D).

Lastly, there’s also the potential for a policy change. Following the collapse of the coalition in late 2024, snap elections are scheduled for February 2025. As of January, CDU/CSU—a center-right alliance of two parties—is leading in the polls and poised to form the next government. The alliance has outlined an ambitious policy agenda aimed at addressing key economic and energy challenges. Its proposed tax reforms include a gradual reduction of the income tax rate, a phased decrease in the corporate tax rate to a maximum of 25 percent, and the abolition of the solidarity surcharge. It also proposes a state-subsidized securities account for every child. In terms of energy policy, the alliance plans to lower electricity taxes and grid fees, expand energy grids and storage capacity, and accelerate the development of renewable energy sources. It also seeks to abolish the

coalition’s heating law that had aimed to reduce emissions. The CDU/CSU also advocates for retaining the nuclear energy option. This includes a review of the possibility of resuming previously shut down nuclear power plants.

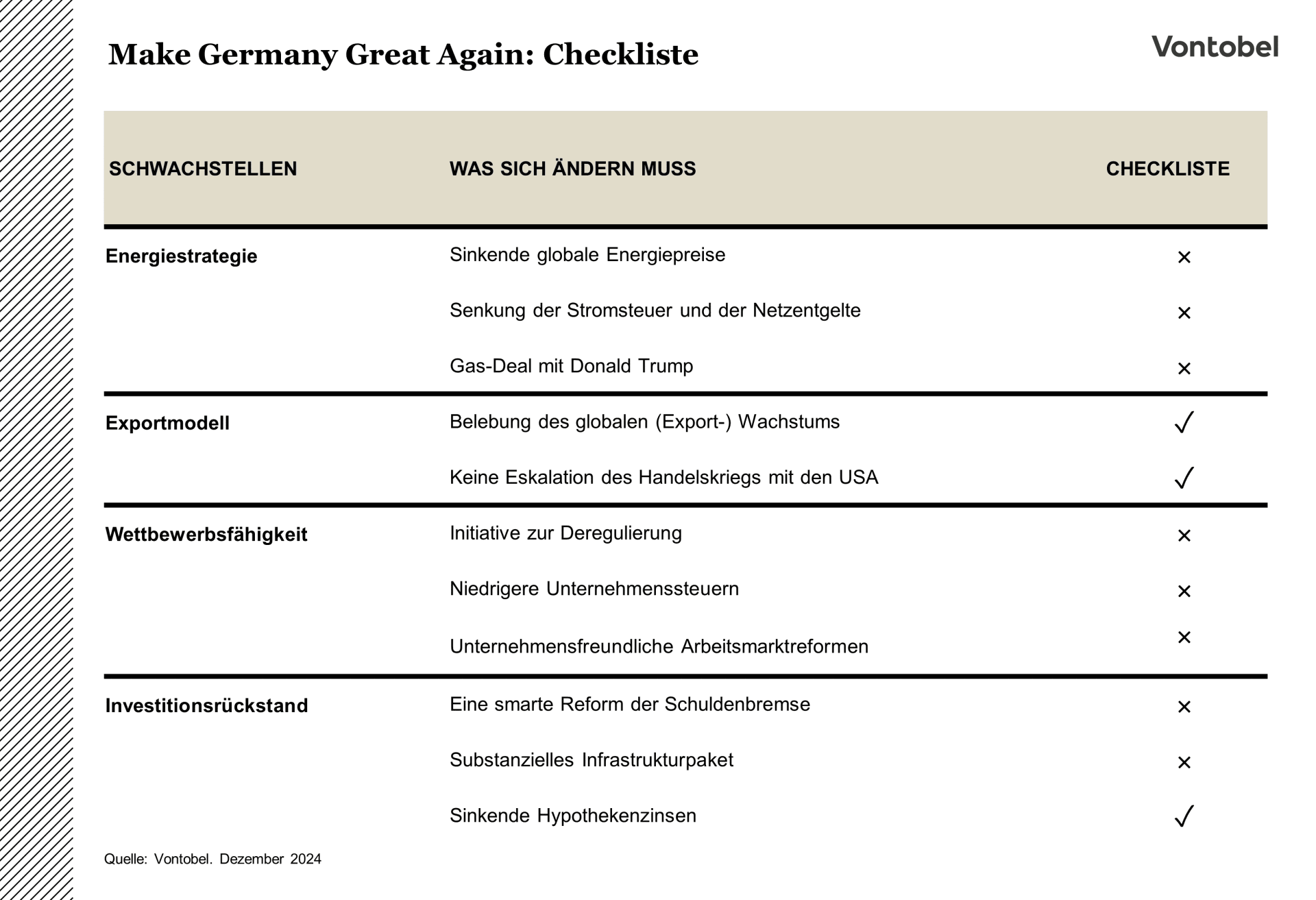

Checklist—what is needed to “Make Germany Great Again?”

To assess whether Germany will one day regain its former strength, the Multi Asset Boutique has developed a checklist that highlights Germany’s pain points and identified what it believes it would take to overcome them. At the moment, only a few criteria (i.e., global export growth pick-up, no trade war escalation with the US, declining mortgage rates) are being met. Nevertheless, with the right tools and thoughtful policymaking, there is potential for Germany to turn is fortunes around and that it could one day be “Made Great Again”.

Pressing pause

In the aftermath of the Federal Open Market Committee (FOMC)’s September meeting last year, most investors had largely assumed the benchmark federal funds rate was headed to 3 percent. However, following the Republican victory in the US elections, market expectations shifted markedly upward, with many predicting rates closer to 4 percent. Today, investors are bracing for the possibility that interest rates will remain at their current levels, with no further cuts on the horizon.

Despite the December quarter-point rate cut aligning with market expectations, the Fed signaled a hawkish stance for 2025. Fewer projected rate reductions, coupled with upward revisions to inflation forecasts, painted a challenging picture. Matters were compounded at the press conference, when Chair Jerome Powell acknowledged that some FOMC members factored in the incoming Trump administration’s policies in their projections—a contradiction to his earlier assertion that the Committee does not engage in guesswork or conjecture. While Fed officials may account for potential fiscal policy impacts, their mandate requires evidence-driven monetary policy. Further rate cuts will depend heavily on labor market developments, especially as inflation continues its gradual march toward the 2 percent target.

Without a full-scale pivot from rate cuts to increases, the 10-year Treasury yield is unlikely to decisively breach the 5 percent threshold. Treasury yields closely track market-implied expectations for policy rates (see chart 1), and markets would need to factor in fresh hikes to push yields resolutely higher. Yet the Fed regards its current stance as already restrictive, while rising yields are sapping momentum in housing and dampening equities, which is why an extended pause is far more likely than a renewed round of tightening.

IG: Little room for excess returns

Further Fed easing may provide some support for investment-grade (IG) corporate bonds. For now, most of the positive news appears to be priced into valuations, leaving the excess return outlook heavily skewed. While current yields offer a decent total-return proposition, there is scant scope for spreads to compress further. Over the past 15 years, there have been only a handful of trading days when IG spreads were tighter than current levels (see chart 2). This suggests limited potential for further tightening and could signal increased vulnerability to negative market developments or economic shocks, as spreads have little room to absorb additional risk.

What’s ahead after the latest market jolt?

December 2024 was marked by a complex interplay of monetary policies, geopolitical tensions, political crises, and economic stimulus efforts, all of which led to mixed outcomes across global equity markets and set the tone for a very eventful January. But what’s next?

While the world was preparing to ring in the New Year with champagne, the “hawkish” rate cut by the Fed in its December meeting somewhat dampened the festive mood. The Fed signaled that rates would likely remain restrictive for longer than markets had anticipated, reflecting ongoing concern about inflation and sending Treasury yields higher.

As a result, investor optimism cooled following a record-breaking 2024, with stretched valuations, and the impending year-end earnings season creating more uncertainty. This increased volatility in equity markets in early January and sparked a rotation moving from the US market to more defensive investment styles and sectors with lower valuations, like the Eurozone or Switzerland. The US stock market saw a notable rebound toward the end of the month, fueled by the optimism around Trump’s inauguration and announcements of major investments in AI. However, the momentum was disrupted when news broke of a Chinese startup developing a highly competitive, low-cost AI model, sending the markets into a temporary frenzy.

Despite the late-January setback and the likelihood of continued short-term volatility—particularly for semiconductor and AI datacenter suppliers—the Multi Asset Boutique remains confident that the next 12 months will be driven by strong earnings growth and unexpected positive surprises. Furthermore, it doesn’t believe investors are facing a scenario akin to the dot-com bubble of 2000, when tech companies were characterized by weak profitability, high debt levels, fragile business models, and inflated valuations. Today’s fundamentals are far more sustainable by comparison (see chart 2).

Crude currents

January served as a stark reminder of how quickly fortunes can change in the commodity world. For months, Brent crude had struggled to stay above USD 70 per barrel. But by mid-January, prices had surged past USD 80 per barrel.

Geopolitics played a central role in driving the rally. In its final two weeks, the Biden administration imposed unexpectedly stringent sanctions on Russia. Targeting two major oil companies, more than 180 vessels, insurance firms, and traders purchasing oil above the Group of Seven’s USD 60 per barrel price cap.

Donald Trump’s impending inauguration and fears surrounding a more hawkish Iran policy added to the price increase. During Trump’s first term, Iranian crude oil production fell from 3.8 million barrels a day (mbpd) to 2 mbpd (see chart 1), triggering a sharp rise in oil prices. If Trump delivers on his “maximum pressure” promise, oil prices could climb further—a pattern often seen when an energy superpower is involved.

Trump’s proposal to impose a 25 percent tariff on all Canadian imports, including oil, also played a role. Combined with a colder-than-expected winter in the US that increased heating oil demand, this heightened supply concerns. Reports of inventories at the Cushing, Oklahoma delivery hub falling to their lowest level in a decade (see chart 2) further exacerbated supply concerns.

While the short-term risks are tilted to the upside, there is still hope that the likelihood of a full-blown oil shock remains limited. The current situation differs significantly from 2018 – 2019, particularly regarding Iran. At that time, several buyers were dependent on Iranian oil, but today, more than 90 percent of Iran’s crude exports go to China, a country that does not recognize US sanctions. Iran’s oil minister has already announced that “required measures have been taken”.

Canada’s role is also crucial. The country is important for US refiners, particularly those in the Midwest, as they specialize in processing “heavy” Canadian crude, not “light” US crude.

Then there’s the prospect of continued weak demand. Key forecasters such as the Organization of the Petroleum Exporting Countries (OPEC) have repeatedly cut their demand forecasts, often citing the weak Chinese economy, the world’s largest oil importer. Perhaps the most important argument against an oil shock is Trump himself, as he is not a big fan of high oil prices.

King Dollar reigns

The US dollar soared 7.2 percent last year, with most gains packed into the final quarter on hopes of a “Trump 2.0” economic boost, battering global currencies. While the greenback’s rally could extend further, uncertainties surrounding US policy timing and economic momentum might curb its ascent.

Two words—King Dollar (see chart 1). In the foreign exchange market, the dollar reasserted dominance, erasing the previous year’s 2.3 percent dip and posting its third annual gain above 5 percent in four years. Most gains came in late 2024 as markets adjusted to potential Trump policy shifts. The rally hammered developed and emerging market currencies alike, with the Brazilian real plunging 21.4 percent amid domestic economic instability and global risk-off sentiment.

The dollar’s path hinges on US economic data and Trump’s reinforcement of an already robust economy. Lingering questions—on fiscal and trade policy timing, reactions to weaker data, and trading partners’ responses—could shift sentiment. While gains may continue, the late-cycle US economy risks a reversal if growth falters.

The euro on the ropes

The euro tumbled 6.2 percent against the dollar last year, with losses accelerating in the final quarter. A strong US narrative drew investors to the dollar, while the euro faltered under political uncertainty and sluggish growth across the Eurozone. Although the dollar remains dominant, its rally is starting to look overextended, prompting speculation about a euro rebound. A resolution to the Ukraine conflict or more flexible fiscal policies in Germany could provide a much-needed economic boost. The most decisive factor, however, lies with the US—any signs of an economic slowdown could weaken the dollar’s grip and present the euro with its strongest opportunity for recovery.

Swiss franc in the spotlight

The uncertain geopolitical landscape is poised to drive renewed safe-haven flows into Switzerland. The Swiss franc remains supported by the country’s robust economic performance, which outpaces Eurozone peers. Even with Swiss National Bank (SNB) rate cuts on the horizon, franc bulls appear undeterred. However, if global risk appetite improves due to easing geopolitical tensions or economic recovery, the franc would likely tend to weaken.

Switzerland’s latest inflation data solidified expectations for a 25-basis-point (bps) rate cut by the SNB in March, with markets expecting further easing. The key question is whether the SNB will repeat December’s bold 50 bps reduction or opt for a more cautious 25 bps. Market sentiment suggests the SNB could ultimately lower its policy rate to a floor of 0 percent (see chart 2).

Authors

Stefan Eppenberger, Head Multi Asset Strategy

Michaela Huber, Senior Cross-Asset Strategist

Christopher Koslowski, Senior Fixed Income & FX Strategist

Mario Montagnani, Senior Investment Strategist